Archive for August 24, 2010

Stephen Vitiello Interview

Aug 24th

August 2010

If you visit Sydney Park in St Peters any time before September 12, 2010, be sure to have a look at the artwork by Stephen Vitiello. Or should that be “listen” to the artwork, for Vitiello is an American sound artist and the auditory realm is his artistic home. The title of this work is The Sound of Red Earth.

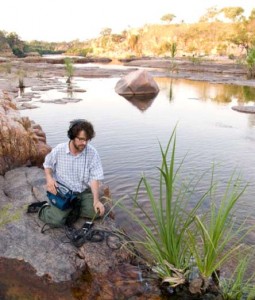

Vitiello, who incidentally had a six-month residency on the 91st floor of the World Trade Centre in 1999, came to Australia recently to record the sounds, rather than the sights, of the remote Kimberley region of Western Australia.

It was the Sydney contemporary art philanthropist John Kaldor who invited Vitiello to Australia, and in accepting Kaldor’s invitation Vitiello became the 20th Kaldor Public Art Project. (See the others, and future projects, at www.kaldorartprojects.org.au)

The day before Vitiello’s work went on show to the public in August 2010, I went to Sydney Park to interview him for the Daily Telegraph. A brisk wind was blowing and it was a relief to walk into one of the three “galleries” housing his work. These pop-up galleries were the three former brick kilns which once made bricks for much of Sydney’s early housing.

In the first of these kilns, the first thing I noticed was the rich red soil brought in from the Kimberley area for the exhibition. The soil was thickly spread all over the floor of the kiln, and it left satisfyingly crisp tracks when you walked on it. Red lights mounted around the lower walls of the kiln accentuated the gorgeous colour of the soil. This kiln was devoted to the sounds of the birds which Vitiello recorded in the early morning or evening when they were most active.

Punctuating the lighter, gentler chirpings that made up most of the recording was the occasional harsh “crawk” of the crow which Vitiello seemed to find watching him wherever he went. Vitiello wasn’t sure what species of birds he recorded, apart from the obvious and ubiquitous crow, but he was attracted by the suggestion that he could invite an ornithologist to identify them.

On to the second kiln, where green lights played on white sand. This kiln was water-themed, and the sounds were of tinkling, bubbling and rushing water.

The third and final kiln, featuring a pinky grey light, was devoted to the sounds of the wind.

“Sound is very much part of contemporary art today, and I always want to bring to Australia what is the latest development in contemporary art,” Kaldor told me.

“I love very much the Kimberley area. It’s only when you’re up there that you really see the grandeur of Australia, the vastness, the open spaces. It sounds trite, it sounds like an ad, but that’s what it is. And the light is different and the sound is different. The Australian landscape has been painted since colonial days by the white people and by the Aborigines since forever. But very little has been done about sound. And I thought it would be great to record the sound of the Australian landscape. And that’s what Stephen’s done. He’s been up there twice for a week, recording different sounds. And this is the result of it. I wanted an international artist but to do something very Australian.”

Kaldor was pleased that, at time of writing, Vitiello was also showing an artwork at New York’s High Line (www.thehighline.org). For that work, Vitiello recorded all kinds of bells in New York – the New York Stock Exchange bell, school bells, the UN Peace Bell and even dinner bells.

“So we really live in a most global world,” Kaldor said.

Stephen was a somewhat intense and focused person, although delightful to talk to. He said Kaldor had been generous in allowing him free rein with his project.

In traversing the vast distances of the Kimberley, Vitiello was guided by a local art gallery owner.

“I had a guide and I was really at his mercy,” Vitiello said.

“The more things would go well, the more he got a sense of what appealed to me. Most people don’t think of sound first. He knows the Kimberley very well, but he’s not a sound tracker or sound guide out there.

“The first trip was driving; the second was on the water. We drove four or five hours a day, then we’d set up camp. I’d wake up before the sunrise and start recording. You’d capture that excitement when the frogs are fading out and the birds are waking up.”

But isn’t the Kimberley – so far from the big cities – very silent?

“No, it isn’t,” Vitiello said. “It often happens to me as a sound artist. Poeple take me some place and they say ‘you’ll really love it, it’s quiet’. But you get there and it’s not quiet at all.”

I suggested that an ornithologist might help him to map the bird-songs in the piece, identifying which birds could be heard. Vitiello was interested, and said he was actually part of a nature recorders’ community on-line. But this type of specificity wasn’t really for him.

“For me it’s much more about the texture, experience and memory than it is about that,” he said. “Although it would be great to have a sound map of what you’re hearing.”

Vitiello discussed his thoughts about sound, as opposed to the visual sense with which most of us primarily explore the world.

“We’re all deeply affected by sound, we just don’t always talk about it or think about it,” he said. “And we’re definitely affected emotionally by sound in a way that’s different than the way we are by a picture. We look at things and we process it intellectually and we say ‘oh, isn’t that a lovely framing of light coming through?’, but it’s very different from the way a sound hits your gut or your skin and it’s also very individual. I feel like sound is much more open. It’s very generous in the way that it allows different types of interpretation.”

Vitiello’s best-known sound artwork resulted from his six-month residency inside the World Trade Centre, which was destroyed in the 2001 attacks on New York.

“The idea was artists were given these studios to use and ultimately my project became about listening to the building itself,” he said.

“I captured the sound of the building moving, creaking and cracking, planes going by, helicopters, storms. You couldn’t open the windows so I learned to use these contact microphones that worked like a stethoscope.”

Vitiello made one of his WTC recordings on the morning after a hurricane had passed through.

“It was safe to go in, but you could really feel the sway. I felt like you couldn’t feel it until you could hear it. One’s perception opened up once you could hear it.”

The WTC recording eventually presented him with a moral burden, given that it took on such a poignant historical meaning following the September 11 devastation. Almost reluctantly, he played his recording to other artists who had experienced a WTC residency, and they encouraged him to do something important with his ethereal “memory of the building”.

The Whitney Museum of American Art invited Vitiello to exhibit his WTC recordings in the 2002 Biennale, which he did, and it later purchased a copy.

Vitiello retains the original, “and I keep responsibility for archiving it”.

Vitiello lives in Richmond, Virginia, where he teaches.