Archive for November, 2010

Richard Goodwin, “Mystic Alien” Interview, Australian Galleries exhibition

Nov 27th

Richard Goodwin is a Sydney architect and artist who undertook a fascinating social experiment/art performance in the Sydney CBD one day in October 2010, on which I wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph.

Richard Goodwin is a Sydney architect and artist who undertook a fascinating social experiment/art performance in the Sydney CBD one day in October 2010, on which I wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph.

For this performance, Goodwin dressed up in a white boiler suit adorned with words and phrases such as “mystic alien”, “porosity researcher”, and “friend or foe”. Accompanied by a small posse of assistants who were there to film and photograph him, Goodwin caught a ferry to Circular Quay from where he proceeded to make his way through the city, finishing at Milsons Point railway station via Town Hall station. He also detoured via several office blocks on his circuitous path through the city.

Just why Goodwin would do all this is what my interview with him was about.

Here is the interview in its entirety, recorded on November 18, 2010, at Goodwin’s Leichhardt studio. This was about a month after the performance/experiment through the city, and we were able to discuss all the things that happened to Goodwin that day.

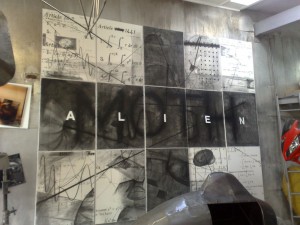

First, an interesting picture I took [left]. Goodwin’s studio was a fascinating place, occupying the ground floor of the home where he and his family have lived for 22 years. I photographed this helicopter section which is normally attached “parasitically” to the wall of his home. He uses it as a reading room. It had been removed for the time being and will be seen as part of the forthcoming exhibition at Australian Galleries in Sydney, of which the documentation of the Alien performance will be part.

First, an interesting picture I took [left]. Goodwin’s studio was a fascinating place, occupying the ground floor of the home where he and his family have lived for 22 years. I photographed this helicopter section which is normally attached “parasitically” to the wall of his home. He uses it as a reading room. It had been removed for the time being and will be seen as part of the forthcoming exhibition at Australian Galleries in Sydney, of which the documentation of the Alien performance will be part.

Elizabeth Fortescue, November 27, 2010

Richard Goodwin:

All my work, it’s kind of complicated, but just to summarise it, I’m an architect but mostly work as an artist. Over 35 years of practice I’ve come to fuse those back together and become the hybrid. So my work is on three scales: the scale of the gallery as a laboratory, the scale of the city as public art or parasitic transformations of buildings. Now that’s different from an extension on a building because in order to be parasitic and to radically transform, it has to break rules like go higher, go across boundaries, make linkages with other buildings, perhaps. Now cities need radical transformation, and so does public art as a site. Because if we’re going to a) survive b) make architecture more intelligent or give it new technologies or make the social construction of the city better, then we need to radically transform. So the radical nature of my practice is to do with rethinking the city and it rethinks public art because no matter how contextual or supposedly appropriate – although I don’t know that art should be appropriate – public art has become, it still ends up being stuff between buildings. So for me the radical and exciting place for public art is the skin of architecture itself. So the parasitic structure attached like a lot of my work does is where wer’e trying to build. It’s a very difficult area. That leads to the third scale I’m interested in which is the city, the infrastructure scale. So the performances always start my projects and they have since 1975. I’m just putting together a series of images for my exhibition [Between a slum and a hard place, Australian Galleries, Sydney, November 30-December 18, 2010], which summarise those actions between 1975 and 2010, and the Mystic Alien is one of a series of about 12 major performances. At the scale of the gallery, I look at where the body ends and architecture begins, so it’s exoskeleton, so it’s about these machines and the body, but not literal like Stelarc, it’s kind of bicycle and a person, a motor bike and a person, a machine breaking up, what does it say about the body, what does it say about architecture, and you can see various pieces of it. You can take that analogy to a building and say a building’s a body. What prosthetics can we add to make that better? You can take that to the city and say, collecting all these new propositions of structure and pushing them through buildings, monorails and doing all these things to three dimensionalise public space, that’s the third scale. Not many artists work on three scales. Not many would be bothered. It complicates things. But I love working that way. I’m not putting it forward for everyone.

Now the place of performance is very interesting . When I was studying architecture it was form follows function modernism, just before post modernism started. So I wanted to break free from that, and through performance art I was able to be most free. Sort of a direct action to start an idea. And I’ve sort of done that ever since because it was part of the 70s. My research which made me a professor has enabled me to study types of public space inside private space. That’s my theory, it’s called porosity. I believe the more porous a city is the healthier it is. Porous just means the public can get inside more. In the age of terror, everything’s closing down. If all these little spaces inside that we can and should be able to go to – corridors, toilets, foyers and stuff – all start to link up better in the city through parasitic structures, the city’s more complex like an Asian city but I think it’s better, more healthy.

When I was studying these spaces inside buildings as a researcher, end game being ‘how do we make more parasitic public art works?’, I was kind of in disguise. The performances were me in an Armani suit, quite literally, so no one would notice me. It’s so dumb, isn’t it? If you wear an Armani suit you can go anywhere. The Alien is the antithesis. I suppose I’m frustrated by what continues to happen and that movement to change buildings, even for the betterment, is slow. My projects, my actual parasites – one I’m just finishing in Elizabeth Bay – are both public art and private architecture extension. [The one in Elizabeth Bay] took six years to get through council, to get through the Land and Environment Court, so the Alien is a little bit of a frustration. Maybe it’s kind of a self portrait…..

Goodwin wore a real astronaut helmet while dressed as the Mystic Alien.

The space helmet which I found by serendipity in Istanbul , which is really Karpov’s helmet, and that’s been verified and researched, you become an astronaut but you also become a kind of an alien. The performance was really, ‘here’s a guy who’s not going to get in supposedly; I’m just going to go and cause trouble. Walk into offices, walk into buildings. But be absolutely just the other. Passive’. I found it very very interesting. I didn’t get put in jail in the end. All my filmers got stopped, but we still filmed anyway. He [the Alien] has signs on his body of all of these conflicts in us. I put all the names on the suit and Mystic fell above Alien and I thought ‘that’s a Mystic Alien’. It references, as my work has in the past, problems about the alien and all our fears. So he just walked about benignly and it had the most bizarre effect. I didn’t get shut down. People around me [his assistants] did. But equally nobody really approached me. They certainly knew I was there. Everybody was buzzing with ‘what are we going to do, there’s a madman [in the building].’ But it was interesting how wary, strangely wary [people were]. Not even inquisitive. Not really wanting to know. I was so surprised at Town Hall station, because they stopped everyone around me and I was waiting for these hands [to come and grab him on the shoulder]. So the poor little Mystic Alien got on the train and went to Milsons Point.

The helmet’s serious. You could say ‘oh well, it’s someone in fancy dress’. But it definitely wasn’t getting a fancy dress response. It’s as simple as that really. It’s not about the audience. Not that I don’t want it known. Anything that gets the debate deeper. People just don’t get what’s happening in the city.

I said to Goodwin that the ‘parasitic structures’ he referred to reminded me of old cities like Florence, where there was a long tradition of grafting new buildings on to existing buildings.

I said to Goodwin that the ‘parasitic structures’ he referred to reminded me of old cities like Florence, where there was a long tradition of grafting new buildings on to existing buildings.

I often say that everything that I’m on about and I like, happens anyway. The big difference now though is that we’re run out of time, we have to accelerate the process. I’ll give you a good examlpe. We built that lovely Aurora building by Renzo Piano, but we pulled down the State Office Block to build it. It was a bronze clad, award-winning building. Build the Renzo somewhere else. In terms of sustainability, we just can’t keep doing that stuff. It’s a coral reef metaphor. We must keep the armature and radically transform. The aesthetics of radical transformation I think is more up to date – grafting new geometries. Because we now have the power with our computer systems to build all these very complex geometries that can fit in all around this rectilinear texture of the city.

You would probably love mouse runs?

The more complex the better. Again, that’s already modelled. Asia’s already doing it. Shanghai where I often take students is starting to three-dimensionalise its public space. In other words, buildings linking up in the air, roads going higher. Not just one ground plane. Public space should be all through the system, and that’s what makes a city healthy. Public space is like oxygen in a city.

Where did you get on the ferry before alighting at Circular Quay on the day of your Mystic Alien performance?

Balmain. [He went first to Customs House and stood on the under-floor model of the city. He then proceeded on foot to Governor Philip and Macquarie Towers.] I caused a bit of a ruckus there but they didn’t stop me. Even the police saw me there. They were gathering.

Goodwin was escorted out of the Renzo Piano building by security staff, went into another building in Martin Place without being apprehended, then went to the Hilton Hotel in George Street where he actually made his way into the corridor system without any trouble. He made it upstairs and into an office.

I did know the people in the office but they didn’t know I was coming. From there into Town Hall station, through the turnstile, and all the time i was filming out of my helmet. [He bought his ticket from a vending machine.] There were some funny pictures of that. I didn’t have my glasses on, and I had to put my glasses over the visor. Here I am deciding what ticket to buy. (use picture here.)

Goodwin caught the train to Milsons Point station. Two of his assistants were still with him, although one had only a mobile phone to photograph him with. He had started off with five photographers.

At Town Hall [station] they were well and truly packed off and people were getting quite agitated. It was a bit anti-climactic in a way. It just shows when you want to cause some trouble, you don’t. And when you’re completely innocent, wanting just to take a photo of architecture … It’s got completely out of hand. All my students are warned all the time that they mustn’t put this stuff on the internet or utube unless they’ve got ethics approval. What isn’t garbage is that you understand that you’re not able to defame people or concentrate on them. To me public space is sacrosanct. The reason I’m so hard core about it is because it is political. In the end it leads to the sort of possibilities in architecture that I find interesting. In fact my work has just been in the Venice Biennale as part of the Now and When visions of what the city will become. It’s not as if this work is not being taken seriously on one level, and yet we’re not doing it.

This parasitic action is based on research. It’s where the buildings might best be combined. Linkages.

Like the aesthetics of the film Blade Runner?

Totally Blade Runner. Sci fi always sees things first. It’s known that humans do cities very well and if you take care of the social construction, humans live happier in high density. Humans are great termites. They do high density really well. And that’s where the world’s heading if we’re going to survive.

Goodwin said people were briefly happy in suburbia in the 1960s, but that was because their doors were always left open. There wasn’t the same level of personal security observed.

Goodwin said people were briefly happy in suburbia in the 1960s, but that was because their doors were always left open. There wasn’t the same level of personal security observed.

The only way to change suburbia is to open all the doors. Cities is my thing, but art allows me to be more radical with it. And art has a great history in changing history. It’s not public art. Trouble is public art is becoming compliant again. It might be all ‘oh well, it’s contextual and site specific’, but if it’s too polite it’s just window-dressing. I mean, art’s sort of the conscience of the city.

What’s the project in Elizabeth Bay?

The scaffolding is in the process of coming down, so you’ll see it. All of my work appropriates things. Takes junk and makes it something else. Even on a big scale. So this timber thing here [he showed me a model] is a wing roof based on a Stealth bomber and it’s on top of this building. This [structure] shades the thing, collects water to do the gardens, uses ventilators so the air conditioning is not always needed. The carbon footprint of the building is 50 per cent less.

From around, the public do see it [so it could be public art]. It’s not an extension because it’s not allowed. So we’re at this point where the elasticity of urban planning must be made more intelligent. Because the debate about architecture, about public art, is just too dumb.

Copyright Elizabeth Fortescue, 2010

Euan Macleod Interview

Nov 26th

On November 3, 2010, I visited Euan Macleod at his home in Haberfield. I was writing a story for the Daily Telegraph, Sydney, about Euan’s survey show at the S.H. Ervin Gallery. Titled Surface Tension: The Art of Euan Macleod, 1991-2009, the exhibition was to open on November 12 and tour to regional galleries after its closure at the S.H. Ervin on December 19.

On November 3, 2010, I visited Euan Macleod at his home in Haberfield. I was writing a story for the Daily Telegraph, Sydney, about Euan’s survey show at the S.H. Ervin Gallery. Titled Surface Tension: The Art of Euan Macleod, 1991-2009, the exhibition was to open on November 12 and tour to regional galleries after its closure at the S.H. Ervin on December 19.

This was not my first meeting with Euan. Indeed, I had first met this artist on the day he won the Archibald Prize in 1999. Winning that prize for his painting, Self Portrait/head like a hole, set Euan on the path to success which he has since followed with a singleness of purpose and a self-deprecating amiability.

After meeting him at the Archibald all those years ago, I interviewed Euan on quite a few occasions when he was having exhibitions or when he had won other prizes. I recall interviewing him at the National Art School on one occasion, where he taught until this year (2010). His students apparently referred to him as “the professor”, and his patient, slightly shambling demeanour would certainly have endeared Euan to them.

So, here is my November 3 interview with Euan, which I have edited only lightly. We sat in the studio he had built in the large, rambling backyard of his home, drinking strong black coffee. Photographer Bob Barker was with us, and he appears in some of the pictures I took myself on that day.

Elizabeth Fortescue, November 26, 2010

Euan said his first survey exhibition had been in Newcastle in 1998, just before he won the Archibald. He humorously contrasted the process of setting up the Newcastle show with the far more white-glove approach at the S.H. Ervin, now that he is a well-known artist.

Euan: [For the Newcastle show] I drove round and picked up a lot of the paintings on the roof racks. This time a lot of people have insisted they are crated on the premises. Some people wanted me to paint replacement paintings. [The 2010 survey show begins with work from 1991 when Euan’s work was still evolving.] The work was very much about the figure in an interior, and I just didn’t deal with the landscape. I didn’t want to.

Later, Euan said, the figure got smaller and smaller and the landscape got more important. Now the figure comes and goes. He also spoke about the new book, Euan Macleod: The Painter in the Painting, by Gregory O’Brien, published by Piper Press, 2010.

It’s a lovely thing to have and I love the way he’s done it. It’s beautifully written.

Euan spoke about the painting called Digging, Painting, Eating, from 2005.

It’s a bit of a reference to [Philip] Guston‘s paintings. A homage to him, really. Those beautiful paintings of him in the studio and smoking. I love those works. He does those big cartoon heads and he’s always got the prickly, you know, shaving. There’s always very personal references to the act of painting, the solitude maybe. That was just a reference or starting point for it all. I think the painting’s in Philadelphia, in a private collection.

We stopped [the survey show] at 2009, so that was just when I was beginning the Antarctic works. They kind of end it. Whereas the book goes a bit further and includes the show I had at Watters.

I sometimes worry that the work that you’re doing, to include it in a show is kind of hard because you’re closest to it so you want it. You say, ‘oh what about this one I did this morning, can’t we put that in?’ But you haven’t had a chance to kind of tell whether it’s any good or not. You look back at it later on and you go, ‘oh fuck they were dodgy works, they were shockers’.

In a way I think you can be too seduced by what you’re doing now and that was the benefit of having Gavin [Wilson] curating the show and Greg [O’Brien] writing the book. I left it pretty much up to them what they chose. Gavin pretty much chose the work for the show. He made the selection. I had a little bit of input, but as little as I possibly wanted and I was really pleased with how he’d worked it out. My problem was so and so has supported me, we’ve got to have one of his paintings in. Whereas Gavin was totally objective. I’m thinking I’ve got to put the same number in from Niagara as Watters [galleries which show Macleod’s work]. So you’re worried about keeping everyone happy. The writer and curator were much more objective than I could ever have been. I would suggest things and say ‘what about this one?’, and they might just look the other way or smile. ‘We might be able to get that one in if the book stretches to 2000 pages.’

In a way I think you can be too seduced by what you’re doing now and that was the benefit of having Gavin [Wilson] curating the show and Greg [O’Brien] writing the book. I left it pretty much up to them what they chose. Gavin pretty much chose the work for the show. He made the selection. I had a little bit of input, but as little as I possibly wanted and I was really pleased with how he’d worked it out. My problem was so and so has supported me, we’ve got to have one of his paintings in. Whereas Gavin was totally objective. I’m thinking I’ve got to put the same number in from Niagara as Watters [galleries which show Macleod’s work]. So you’re worried about keeping everyone happy. The writer and curator were much more objective than I could ever have been. I would suggest things and say ‘what about this one?’, and they might just look the other way or smile. ‘We might be able to get that one in if the book stretches to 2000 pages.’

Actually the writer, he changed. There were works he hadn’t liked as much initially and he grew to like them a lot more. For myself I think that was interesting because I’ve been a little bit, not dismissive of them, but I wondered about them myself and it was actually nice that he grew to really like those ones. The ones that were much more chaotic. [Like the work depicted on the back of the book. It is titled Starry night, 2002.] I literally poured the paint on. That’s a wee self portrait. It’s hard to see.

The Archibald painting is in [the survey show]. UTS owns it. I must say I was wondering about putting it in. Because of the intensity of that whole experience [winning the Archibald] I grew to hate the painting. But I suppose in doing the book both the writer and curator were quite positive about it and it was an opportunity to see it in context rather than just seeing it as an isolated work, because in the Archibald it was totally taken out of context. it was seen on its own, no one ever realised it was actually related to a whole group of work. So it’s a little bit more of reclaiming ownership of it I suppose. When I see it in the show I might not think that. I might go, ‘ooh’.

Was it actually part of a series?

Yeah. And this one where the figure’s hidden. It was actually a bit of a piss-take because it was that idea of new age painting where the figure is incorporated into the landscape where you have the woman lying down and she becomes part of the hills. It was actually a bit of a reference to that kind of work. That’s what the dolphins were implying. But no one really got that. Too bad, my irony didn’t work. I don’t think I’m a very good post-modernist. At the time [of winning the prize] it was quite hurtful, the whole process. People said some really nasty things.

[I commented that Euan’s win had also been very popular among many people.] It’s better to have won it than not, though?

Yeah. I was saying to someone else that I wish I had been able to distance myself from the prize a little bit more in that I took it too seriously. Whereas I don’t think a lot of people do take it seriously. But as an artist to be able to distance yourself from your work is very difficult. You’re desperately trying all the time not to do that, to be close to it. Especially being a self portrait it encourages that whole idea [that] if someone’s criticising the work they’re actually criticising you. And they’re not. If I criticise your writing I’m not saying you’re a bad person, but it feels that way.

Euan entered the Archibald on only one subsequent occasion, with a portrait he did of Frank Croll, who died soon afterwards. He has no desire to enter again.

I just feel it’s best to leave it to someone else. You’re sort of taking up someone’s spot. And I didn’t enjoy it the first time. I didn’t want to ever enter it again, but it was just this one guy. It was the most amazing experience because he was terminally ill. It was an amazing interaction. He was a heart specialist and his one regret was he hadn’t been able to paint. I said, ‘mate, just do it. You don’t need to show anybody.’ Because a lot of collectors are frustrated artists in a way. They are people that wanted to do it themselves and for whatever reason felt they weren’t good enough and by buying [artists’ work] you’re doing the worst thing. You’re buying the best examples. It’s like thinking ‘what shall I paint? I’ll go along to the National Gallery in London and get a few ideas’, and you’re just totally humbled.

Is the survey show comprised only of paintings?

Is the survey show comprised only of paintings?

In the show we’ve got a couple of works on paper, en plein air. They’re the ones I did on the boat. And the group that won the Parliamentary Prize. Whenever I go on holidays or things … [Euan showed me a stack of plastic, segmented fishing tackle boxes which he fills with acrylic paints of many different colours and takes with him en plein air.] You can open it up and the paints remain dry. You can carry them around. You can take them overseas, you can do anything with them. I go out, open it up and you’re painting in about two seconds. It’s fantastic. I’ve put hundreds of people on to them. They’re fishing tackle boxes. I just take one. That’s a really old crappy one. Once they’re used up you can just peel all the paint off and reuse them. I normally use oil (on the canvases.) A lot of the stuff when it’s drying I can scrape it on. You can put it on like that and you can get a lot of nice texture with it. You’re getting a bit of grit and stuff on it. I love it sort of drying up. It’s fantastic.

How long have you lived in Haberfield?

How long have you lived in Haberfield?

We moved here about 10 years ago. Built the studio. Probably about half the show [has come out of this studio].

I don’t have a set working pattern. You know how some people work nine to five. I don’t do that. It’s probably more when I’ve got time. I’ve been finding the business side of it takes a long time. The show and the book have been incredibly time consuming. I worked up until this year [at the NAS].

Has it liberated you not to have a job?

No, only because of the show and the book have taken up most of the year. They have been very time consuming. There’s an irony to that really. That public side of it all. It’s been important to me to keep into the studio as much as I can, but it has felt like grabbing time to do it.

After the show will that change?

I’m certainly thinking it will.

Tell me about the large figure seated in the landscape; sitting on the coastline.

I wish I had been able to put more in. In the book that’s one of the periods where there’s not so many of them. They’re kind of giants. I wanted the scale to be slightly ambiguous and see that blue thing is like a head, a face, which is my father’s head. And that’s a reference to this painting which is far more obvious. That’s my father’s head. I guess he looks a bit like me.

There’s all sorts of connotations. There’s a personal mythology and a public one. That’s something Gavin pointed out. In a way I see them as him [my father]. The big figures. He’s kind of lost, in a way. He had Alzheimer’s so he was lost. When he died my mother brought him home. We’re not that religious and we’re certainly not Catholic and yet she had him laid out in a coffin exactly where the boat was. [Euan’s father had built a yacht inside the family home in New Zealand. When it was ready to be launched, Euan’s father actually dismantled the front window of the house to get it out.] I don’t think she thought about it. That’s a painting that I did of it up there. I made it a boat. It was just a coffin. With the boat pointing out the window. Which is kind of beautiful. There’s something very poetic about it. I guess it’s become a bit clumsy now in terms of the retelling of it. But a lot of that came out in the painting. Like I painted him in the boat but you think about it and it’s obvious to put him in the boat. He built it and he sort of gave birth to it through the window. So there’s lots of references to that in here. Possibly more in the book.

Part of it was that idea, and the road, too, where the son’s looking at the dead father and thinking ‘how am I going to go on?’. There’s that sense of the father.

Were you close to your dad?

No. And probably the painting is a way of connecting. I don’t think I ever quite knew him, or vice versa, actually. He got sick when he was quite young. I remember being down in Rozelle Bay or wherever it is and there was a guy standing up in his dinghy which of course you’re not supposed to do, and it really inspired me. I went home and painted. But of course there’s that photo [of his father standing up in his dinghy]. It’s fascinating. So I think a lot of painting is pulling images up from the subconscious and they probably have some kind of meaning on some level but I guess the trick is not to make them too personal otherwise other people think what a big wank. So it has to have some kind of universal significance in some way. But so many people have said to me, ‘my dad was into boating’. A shared history, I suppose. But the whole idea of the boat. It’s fascinating. Just as a means of transport. Going from one place to another, which the walking figure is as well.

What about the walking figure trailing clouds of smoke, which is often in your work?

Yeah, I don’t know what that was all about.

[I said I like not knowing in a way, because it allows the imagination to wander.]

[I said I like not knowing in a way, because it allows the imagination to wander.]

That’s a lovely way of putting it. If you tried to work it out, once you think, ‘oh that’s why I put the boat in the room’, when you paint it next it’s illustration. You’ve got to be careful it’s not illustration. It was Philip Guston I think who was going on about not wanting to know where all the stuff came from, almost as if it would kill it off. I don’t know if I agree with that, but there’s a fear of …. I think you keep coming up with mystery. I don’t think you know everything. There’s a big wide world. But it is fascinating on that private level just how things come out, and where they come from.

Certainly I love that idea of a relationship between the figure and the landscape, trying to keep it fresh, thinking in terms of the figure as clouds or the materiality of the figure.

Copyright, Elizabeth Fortescue, 2010

MCA building works

Nov 21st

I took this picture at the Museum of Contemporary art this week. It shows some of the work that is going on at the site. The $50 million project will extend the MCA and give it a new entrance, cutting edge education centre, sculpture terrace, cafe and more.

I took this picture at the Museum of Contemporary art this week. It shows some of the work that is going on at the site. The $50 million project will extend the MCA and give it a new entrance, cutting edge education centre, sculpture terrace, cafe and more.

Elizabeth Fortescue, November 21, 2010

Sculpture by the Sea, 2010

Nov 6th

If you haven’t already been to Sculpture by the Sea this year, go now. It closes on November 14. I wandered along the dramatic, brooding coastline on a recent rainy day and took these pictures of a small selection of the 108 works of art on view. The rain started pelting down before I could do the entire walk, so I had to abandon ship. I’ll try to go again and take some more images of the Tamarama end. Hover your mouse over each picture to get the artist’s name and title of the work. David Handley, the founding director of Sculpture by the Sea, told me this year that it costs the contributing artists an average of $15,000 each to be part of the event. This amount is made up of materials, construction, transportation and many other on-costs. So a huge thank you to all of the artists. Of course, the sculptures are for sale.

If you haven’t already been to Sculpture by the Sea this year, go now. It closes on November 14. I wandered along the dramatic, brooding coastline on a recent rainy day and took these pictures of a small selection of the 108 works of art on view. The rain started pelting down before I could do the entire walk, so I had to abandon ship. I’ll try to go again and take some more images of the Tamarama end. Hover your mouse over each picture to get the artist’s name and title of the work. David Handley, the founding director of Sculpture by the Sea, told me this year that it costs the contributing artists an average of $15,000 each to be part of the event. This amount is made up of materials, construction, transportation and many other on-costs. So a huge thank you to all of the artists. Of course, the sculptures are for sale.

Elizabeth Fortescue, November 6, 2010