Archive for April, 2011

Backstage at the Archibald Prize: paper planes and steel-plate etchings

Apr 17th

When Ben Quilty won the Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW in Sydney yesterday [April 15, 2011], it was less than a decade since he had received his first real career boost – the receipt of the 2002 Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship. And Margaret Olley, one of the judges of that scholarship in 2002, was the very appropriate subject of Quilty’s Archibald winning portrait. Both artist and sitter were at the gallery when the $50,000 prize was announced.

When Ben Quilty won the Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW in Sydney yesterday [April 15, 2011], it was less than a decade since he had received his first real career boost – the receipt of the 2002 Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship. And Margaret Olley, one of the judges of that scholarship in 2002, was the very appropriate subject of Quilty’s Archibald winning portrait. Both artist and sitter were at the gallery when the $50,000 prize was announced.

Quilty’s two young children, Joe and Olivia, made paper planes from copies of the press release, their youth somehow showing how an art prize that is 90 years old is still going strong. I observed all this as the visual arts reporter for the Daily Telegraph.

I first met Ben Quilty many years ago when he was just starting to exhibit his work to the the beginnings of what would become acclaim. It must have been just after he won the Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship in 2002. Right back then, it was obvious he was a young man going places. And boy, could he paint.

I thought he would win the Archibald a few years ago when he entered a wonderful portrait of Beryl Whiteley, who established and endowed the travelling scholarship in her son’s name. It was a great painting of Beryl; so full of steely determination and the will to survive, no matter what. I saw the painting in Ben’s studio, which was then in Alexandria. Ben would miss out that year, although his portrait of Beryl Whiteley did make it to the finals. But this year he has stormed home with his wonderful evocation of that grande dame of Australian art, Margaret Olley.

There was a definite sense of history and the passage of time yesterday when Ben was announced as the winner of the 90th Archibald Prize. Margaret Olley, of course, was the subject of William Dobell’s 1948 Archibald Prize winning portrait. At that time, Olley was a young unknown, just about to leave for Europe for the first time and embark on what would become a long, sometimes bumpy and richly creative life.

Yesterday, there she was again, this time as a near legend, as well known for her own lifetime’s artistic output as she is for her remarkable philanthropy. Edmund Capon, director of the Art Gallery of NSW, told me yesterday that Olley’s gifts of local and international artworks to the AGNSW are in the vicinity of $8 million. Some of those gifts to the gallery were paintings by Quilty.

You can see what attracted Olley to Quilty’s painting in the first place, when she and AGNSW curator Barry Pearce were judging the 2002 travelling scholarship. There’s a love of the creaminess and viscosity of paint, a deftness of application, a daring to be different, and a dangerous edge to the subject matter. Sometimes Quilty has gone too far, however. Accepting the prize yesterday, he admitted that Olley hasn’t always liked what he’s chosen to paint. Quilty has specialised in painting the emblems of young Australian male angst – human skulls with cigarettes clamped in their jaws, or revving Toranas. Olley had visited his studio one day and, seeing his latest works there, had asked what he was doing. “Experimenting,” Ben had replied. “Well, stop experimenting,” Olley had told him, characteristically to the point.

In return, Ben had a nice story about Olley. “Recently I was amazed at how many new works she had on the go,” he said. “She said to me, ‘I’m like an old tree dying and setting forth flowers as fast at as it can, while it still can’.”

If Olley is urging Quilty to “celebrate life” rather than death, then she’s leading by example.

I finally got my interview with Ben after all the radio and televisions stations had done their live crosses. Here’s what he said:

Why Margaret Olley for the Archibald?

Because she has been such a long time mentor for me. She’s someone who seems to incongruous with my practice. Which I actually now like. Why not? You’re meant to be able to do whatever you want as an artist, and in the past I have felt very in a way very sort of controlled in my choices, just to continue to fit in with what is deemed contemporary. When she said that comment about the old tree, I thought “that’s amazing, what a human”. It was so powerful. She suffers from depression, and I would instantly link [depression with a] fear of death. But it’s not. She gets depression but she has the healthiest regard for her own mortality. And that’s what my work’s been all about. Especially young male mortality and what it means to be a young man.

She supported you all through your skulls and Toranas, but she didn’t really like them, did she?

No, no, no. She’s always said to me “you should make paintings about a celebration of life, rather than this dark, introspective paintings about male youth”. And I always stuck to my guns and said “well, Margaret that’s what I do, that’s what my experience is”. And I’m sure I will come to a different point in my life where I am celebrating my existence, but at the moment I’m mkaing paintings about my experience about young masculinity and I feel like they’re a part of society that is voiceless and they need to be heard, and I’m the person that can help that happen by talking about it. No one talks about that stuff, and it’s brutal and awful and a devastatingly difficult thing to live through as a young man. So Margaret understood that, but she also said “why can’t you talk about those things by celebrating life and showing that you’ve come through it?” So we’ve always had this discourse and a very healthy regard for each other’s point of view but also not entirely agreeing with each other, which is what it’s about. It’s about challenging each other. She was totally fine with me to keep doing it, she’d just pull me up every time I did and say stuff like that, “stop experimenting”.

You’ve started a series of portraits on Kylie [Ben’s wife, pictured left]. Is that a concession to Margaret?

You’ve started a series of portraits on Kylie [Ben’s wife, pictured left]. Is that a concession to Margaret?

No, that’s a concession to Kylie. In one show I had last year called Inhabit, that was a very dark show, very dark, and it was a very hard year for me for a number of reasons, personal reasons and stuff, and she [Kylie] said then “you live with these paintings, you’re in the studio all day every day, with these works, sort of growing, but growing on such a dark tangent. You need to make something beautiful”. And it was a good point. It’s the same as what Margaret said. As a contemporary artist why can’t I make something that’s beautiful and it be just as important as something that’s rigorously negative? And part of me thinks that that’s a Catholic upbringing. I went to a Catholic high school, and the idea of guilt, maybe it’s something to do with that, or entrenched Catholic Irish guilt from generations ago in Ireland, that I feel like as an artist that I have a responsibility to do more than just be covered in paint but to actually make comments about things that I feel. And I feel strongly about a lot of things, particularly the environment, and I spoke to Margaret at length in the lead-up to this Archibald and said “if I do win I want to talk about the environment and the fact there are people who still deny humans have anything to do with it”. She said “Ben, I agree, it’s ridiculous. I wouldn’t even address it because they don’t deserve the time”. But I said to her, it’s like denying Aboriginal people the vote. That’s how it will be seen in years to come.

Like the flat-earthers.

Exactly the same. It’s bizarre that I’m living here now and seeing it happen, and I just want to muzzle them and say “you guys are doing intense damage to my grandchildren’s lives and it’s time you stopped.”

Did you do this painting at Margaret’s house?

No, I actually made a steel-plate etching of Margaret. The marks that are on her face that are contained inside that shape, I actually did a hard-ground etching with a scribe and I just put in these little tiny marks and I wanted to leave her face blank. In fact, my idea was to leave even less marks on her face, the purest couple of little marks just to define her face. It’s hard for me to stop. The plate did that really. I also took photos and did some drawings. But scribing those marks, particularly that left eye, it’s Margaret. When I looked at it I thought , “I’ve drawn this wrong”, and I went back and photographed Margaret again. She looks at you with this piercing eye, and it’s so Margaret.

Is it raw canvas that shows through between the areas of paint?

It’s pre-primed linen.

What did you apply the oil paint with?

There’s everything. Brushes, and palette knives, and I scraped it off.

Do you feel this is an historic moment, given Dobell painted Margaret to win the Archibald in 1948?

Yeah, it is so amazing. [Ben said Margaret opened up to him with wonderful stories about Hill End where she worked with her great friends Russell Drysdale and Dobell.] She just opened up and told me all these very private stories about Russell Drysdale and Dobell. They’re like my mythical heroes, but they’re mythical, they don’t exist. There’s no recorded video footage of them, there’s no audio. And she’s it. She’s this portal to this period so long ago which has really informed who I am and what my work’s about. I’ve been looking at the Rabbiters painting from Sofala since I was about eight and it had such an emotive resonance for me.

Is your painting of Olley for sale?

Um, no.

Are you keeping it for yourself?

I don’t know. I’ve just been pulled aside then because people are talking about trying to buy it.

How does today compare with 1948?

How does today compare with 1948?

Well, I can cope with it much better now than I did then. Then I was just at the beginning of my career and I was on my way to Europe. So all that publicity when I came back, it took me years to be able to look at it. Here I’m at the end of my career, and I’m so pleased Ben won it. It’s a terrific painting. Barry Pearce and I gave him the Brett Whiteley scholarship, and I think that’s helped him.

How do the two paintings of you compare?

I’m a different person. I think the one Dobell did of me is the best Dobell. And I think this [Quilty’s work] is a great, great painting.

ArtWriter also sought Edmund Capon’s opinion.

You can’t go past that picture [the Quilty], but there’s a lot of good pictures this year. It’s one of the best Archibalds. It’s a very good show.

Your favourites?

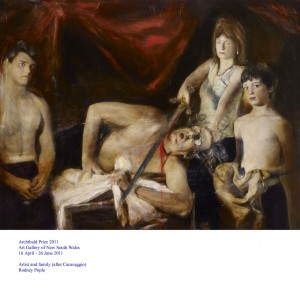

Obviously the winning one. I like Jun Chen’s portrait, I like Charlie Waterstreet’s portrait by Adam Cullen – I’m alone in that. I like Tim Storrier’s and I like Rodney Pople’s and I like that one of Gemma Ward, too. So apart from the winning picture I seem to be somewhat out of step with the trustees. How unusual!

Below are a few more pictures I took at the announcement.

Elizabeth Fortescue, April 16, 2011

Vincent Fantauzzo wins the Packers Prize

Apr 8th

Vincent Fantauzzo won the Packers Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW today, with this portrait of the Sydney chef Matt Moran.

Vincent Fantauzzo won the Packers Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW today, with this portrait of the Sydney chef Matt Moran.