Archive for February, 2015

Chuck Close talks to Artwriter about his hit MCA exhibition in Sydney

Feb 10th

With the Chuck Close exhibition closing at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia on March 1, I’m posting a full transcript of my interview with Close which took place on Skype. Close was in New York, and it was just before the exhibition, Chuck Close: Prints, Process and Collaboration, opened in late 2014.

With the Chuck Close exhibition closing at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia on March 1, I’m posting a full transcript of my interview with Close which took place on Skype. Close was in New York, and it was just before the exhibition, Chuck Close: Prints, Process and Collaboration, opened in late 2014.

First, a little background.

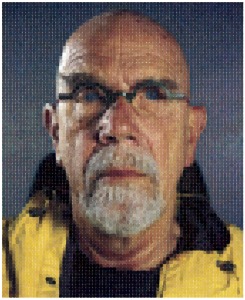

Chuck Close is one of America’s most celebrated artists. His life and work are already the stuff of legend. Close was born in Monroe, Washington, but has lived for decades in New York City. He is, at time of writing, in his mid 70s. His practice is marked by relentless innovation, constant evolution and, paradoxically, a return to the same source material which has sustained and nourished a vast body of work across five decades.

Right from his earliest days as a young artist in New York, Close was openly ambitious. He didn’t care about selling work to private buyers, he would say. He wanted to see his work in major public galleries. Before too long, he got both. Close quickly drew attention with eye-popping portraits of family and friends. These were not portraits in the traditional sense. These were a thrilling take on the centuries-old technique of the grid, used by artists to transfer an image from one surface to another. Close threw his portraits on to vast canvases, awing his audience by the size and colourful virtuosity of his work. He possessed a superhuman understanding of the eye’s ability to mix myriad individual blobs and lozenges of colour into naturalistic shades that mimicked living flesh, sparkling eyes, and unruly hair. Close became, very quickly, a darling of the art world.

By 1988, Close appeared to have it all. A wonderful wife and young family, and an address on the Upper West Side of Manhattan where many of his neighbours were famous. He commanded a coveted place in the stable of artists at New York’s prestigious and experimental Pace Gallery. His paintings were feted, and he was in demand.

But “the Event of 1988” – Close’s description – changed everything.

One day that year, after walking through Central Park to a function, Close was admitted to hospital in horrendous pain. He was suffering a spinal artery collapse, and almost immediately it robbed him of all movement below his neck. Close was now a quadriplegic, facing many months of excruciating therapies before he could return home to an entirely new life. This is where Close’s fighting spirit came to the fore. Even if he had zero movement of his limbs, he said, he would still work. Even if he had to spit paint at a canvas.

Slowly and painfully, Close regained limited use of his arms. He painted with a brush strapped to his right forearm, his left hand being used to steady the right. And so, bit by bit, Close reclaimed enough motor skills to keep working.

So, now you have a little background, here is my interview with this amazing artist:

It’s miraculous that all the plates and other paraphernalia of printmaking, on view in the Sydney exhibition, survived.

Yeah, from the very beginning I loved that stuff. I kept the plates that I’d used in college and graduate school. I didn’t know if anybody else would share my interest but I would keep them with the hope that some day they could be (in a show). I never clean up; I never throw anything away. When Terrie (curator Terrie Sultan) came to me with the idea of doing an exhibition, and I’d just had a painting retrospective, I said ‘we’re not going to be able to borrow a painting because no one will lend them again’, so we had to do something else, and I said ‘there’s this wealth of material that I’ve hung onto all these years and I have a feeling people will be interested in seeing it because embedded in the detritus of various projects is information on what I what I was trying to do’. I was firmly convinced that people really want to know how art happens. They wouldn’t have a clue; they don’t know. When it opened in Houston I didn’t have a chance to find out whether or not people spent any real time looking at that stuff. The second show was at the Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) so I kept running into people on the street who would tell me that ‘I’ve seen the show three times’. That just doesn’t happen. And then I would hang out at the show and watch people looking at the art. We purposefully did a minimum of signage. And I would watch people go down the line of progressive proofs and I could tell they were trying to figure out, ‘oh, this colour went on top of that colour and that made that colour’. As a matter of fact, we got 10 letters written to Nan Rosenthal the curator of the Met, saying that (with one of the works) progressive proofs 6 and 7 were reversed. Now I had lectured in front of that series of proofs five or six times and I hadn’t noticed. So if 10 people care enough to write a letter to a curator, how many more people noticed but didn’t bother to write a letter. I would think a significant number of people are actually looking at it that hard, harder than I was! And it totally mimics the process. You can see colour separations that are photomechanical and it knows all the steps you’ve got to take to get there. It will lay them out for you. I didn’t know which colours I was going to have to do. I knew the first 3 colours…. Then I looked at it and thought, ‘Oh God, it’s going to need some more orange, more green, more blue’. I didn’t know it was going to be 16, 14 colours.

Were you systematic in keeping the artefacts?

Were you systematic in keeping the artefacts?

Well, I was as systematic as a slob can be. I put them in a portfolio, labelled it, you know. I thought at the very least they had souvenir status and that they’d sort of be interesting on that level.

Are you precious with these objects now when you’re using them?

While I’m working they’re laying on the floor, they’re pinned on the wall. I don’t always keep all of the woodblocks because there’s so many of them. I just keep a representative sample of them. So we pick, like for Emma woodblock, I think we picked about eight. If we put them all up, it would have taken a huge wall.

With the time chart for the spit bite print, I wondered whether you were talking about the amount of time the plate is being immersed?

You’re absolutely right. It’s the time they’re going to be in acid. Once I had a self portrait watercolour, anyway it was the first one ….. black and white and greys, …. So I punched holes with the hole punch …. I would then put it on top of the watercolour …. If I could see the dot, it was a little lighter or darker. If it disappeared it was the same. So I digitised by hand, not photo mechanically, all those greys, and I had a list of numbers. I mixed buckets of paint that matched the grey scale. I ended up with 24. 24 buckets from white to black.

Terrie Sultan says you don’t enjoy lithography. Why?

Well, you’re just drawing on a stone with a greasy crayon. But it’s not going to print the way it looks on the stone. Let me explain: lithography is chemistry, it’s not real. It’s as elusive as chemistry. Are you a cook? I’ve noticed that cooks are either chefs or they’re bakers. Baking is like lithography; it’s chemistry. If you screw up, a little too much something or other, you can’t fix it. But if you’re making a stew (you can add this and that to adjust the flavours). That’s what you can do with stew as you slowly move towards what you want. You can’t do that with baking a cake. It has to be exactly right because it’s a chemical reaction. When you make an etching, you can get your fingernail into the groove. With a block, you can tell how rough something is. But with a lithography stone there’s a tendency for it to be slightly greasier. And I’d be proofing and I’d like the way it was. Then when they want to edition it you’d have to counter-etch it and activate the block again ….. It’s a nightmare. …. It’s not real to me. There’s no rough-cut surface I can see. I’ll tell you a wonderful story about Aldo (Crommelynck), the French printer. So we get through the whole thing and we proof it for the first time and I say ‘it’s not dark enough, I want you to change the ink, increase the pressure and we’ll heat the plate up to release the ink in the plate’. …. Americans, we’re used to doing that. He said, ‘if you wanted it to be darker you should have made it darker. I only use one ink, one amount of pressure, and I never heat a plate’. …. I said ‘that’s all well and good but the thing is not dark enough’. So when he wasn’t there we changed it, but it’s typical of a particular kind of professional printmaker. They can really drive you nuts. I wanted to make a better proof and I’m willing to do anything to get that to happen. I didn’t want to waste that plate; I just wanted to get more out of it. When I was Gabor Peterli’s assistant at Yale, I only made monograms. I was only interested in the first one. I would do anything to get that print to look right. But then I went to work for (I couldn’t catch what he said here), and I was supposed to make 50 prints that looked exactly alike and I had no patience and I was a slob, so I got fired the first day. And he said, that’s alright kid, you make your own prints one at a time, but it’s not going to work for me. The traditional printer wouldn’t have any idea working on one of my monoprints how I had done it.

Because you massaged it to be the way you wanted?

Because you massaged it to be the way you wanted?

Like paint; like paint does. Bob is in the show, and also Keith. The MoMA gave me a show about the making of that one print (Keith.) It’s the first print I made as a mature artist. Then it went on the wall and everybody liked looking at it. So I said, ‘people really want to look at this stuff’. Now (museums) find themselves doing it because they’ve found Matisses and Picassos and other people’s progressive proofs. They’ll sometimes put them up and show them. At the time, they weren’t interested. The plate (for Keith) had oxidised and every fingerprint and everything. Like a dark chocolate patina. So I told the art handlers ‘help me take it off the wall, I’m going to go clean it’. They said ‘you can’t touch that’. I said ‘why not? It’s mine’. They said, ‘well the union requires that anything moved in the museum is moved by an employee of the museum’. So I watched when they went to lunch, and the next day a friend of mine took the plate down off the wall, we went to another floor into the men’s room, took it into one of the stalls, and I cleaned the plate with Brasso, cleaned the whole plate, then I sprayed it with fixative and we took it back and put it on the wall. They said, ‘what happened to this?’ (I said), ‘I don’t know’. (He hasn’t seen the plate since MoMA.) I’m so disappointed (that I couldn’t travel to Sydney) for many reasons, chief among them was seeing the plate and the proofs again. I always think of a retrospective as being a – what happens when a family gets together for a special occasion? A reunion? I think of it as a reunion and all of my children come together who I’ve made individually and I see them together. So I haven’t had a reunion with them.

(Close said he had never visited Australia).

I couldn’t risk my health. You know why I was taking a nap? In the morning I get up, have breakfast, work for a little bit, lie down 11 till 1, or get pressure sores, bed from 3 to 5, dinner between 5 and 7, back to bed from 7 to 11, get up, go back to bed and sleep all night. So all those hours I have to not be on my rear end, which is a colossal waste of time.

Elizabeth Fortescue, February 10, 2015

(My thanks to the MCA for the images used in this post.)