Archive for August, 2014

Archibald Prize 2014: Fiona Lowry captures Penelope Seidler lost in thoughts of her home with Harry

Aug 25th

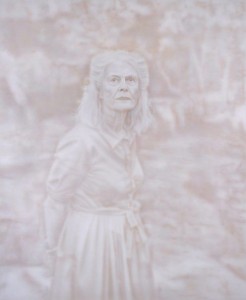

Penelope Seidler with her Fiona Lowry portrait on the day it won the 2014 Archibald Prize. Pic: Elizabeth Fortescue

It’s Friday July 18, 2014, the day the portrait of Penelope Seidler wins the Archibald Prize for Bondi artist Fiona Lowry.

Even before the noon media announcement by Art Gallery of NSW head of trustees, Guido Belgiorno-Nettis, we all know who’s won. At least, we think we do.

Penelope Seidler, widow of the towering Sydney architect, the late Harry Seidler, is in the gallery along with the media. She looks apprehensive.

Across the room, Fiona Lowry can’t help grinning. I key into my Twitter account the words, “Fiona Lowry wins the Archibald Prize with her portrait of Penelope Seidler”. My finger has only to wait for the words. A fellow journo sees what I’m doing and prods me with his elbow. We share a tiny chuckle. Lowry is an obvious winner, and her body language says it all.

Sure enough, a couple of seconds later, Lowry wins the prize. Her portrait is a gorgeous thing. A study of a woman captured in that split second when she looks back at the Sydney home that she and Harry designed and lived in for decades. It’s where they raised their family. The store of memory must be tremendous for Seidler, and her expression in the portrait shows it. She is lost in the moment.

That frozen moment came about on one of the occasions when Fiona and Penelope visited the Killara house on Sydney’s bushy north shore. This was after Fiona had decided Penelope would make a wonderful Archibald portrait, and Penelope had agreed to sit for it.

Penelope Seidler, by Fiona Lowry. Winner of the 2014 Archibald Prize

The house was built in 1966-1967, and Penelope lived there with Harry until he died in 2006.

I spoke to Lowry on Archibald day, when the surreal nature of winning the prize was still fresh. We were about to begin our interview when Lowry’s dealer, Martin Browne, darted in to say one of the posh interior magazines wanted to do a spread on her. Browne said goodbye, and left me to speak to Lowry. It’s started already, I thought. The celebrity thing.

The first time I met Lowry, she was in the Primavera exhibition of young artists at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in 2005. Lowry’s paintings were full of foreboding, quite disturbing. As well they might be, since they depicted people in landscapes where fearful crimes had taken place.

“Yes, I guess it’s evolved since then,” Lowry said when I reminded her of meeting her at Primavera all those years ago. “I’m less likely to go into such a horrific space, but I’ve been taking people down to Bundanon, Arthur Boyd’s property, and spent a lot of time down there making work. I love that history that’s there. So I guess with this one I wanted to take Penelope back to a place that obviously has that history. It’s an amazing space.”

I mentioned that Max Dupain had taken a picture of Penelope in the garden of the Killara house in 1967.

“I know, it’s an amazing synergy and I didn’t know that,” Lowry said. “She told me this morning. I know that photograph actually, so it’s kind of beautiful that it all came together. I do know that photograph but I didn’t know that it was taken down there.”

Lowry knew quite a lot about the Seidlers before she approached Penelope to sit for her.

“I had been a fan of Harry Seidler’s for a long time. I bought his book The Grand Tour when I was younger. I always remember (Harry’s) brother told him to buy a decent camera. He bought this Leica camera and it was all his travels around the world and he took amazing photos of buildings.”

Lowry said she made a point of visiting some of the same places while she was in Europe, using the Seidler book as a kind of travel guide.

Penelope Seider had seemed a powerful figure when Lowry first saw her at an art gallery opening. Later, as she got to know her sitter, Lowry found her “so welcoming and just adorable”.

“I really love her, actually,” she said.

Lowry was already using an airbrush back in her Primavera days, and she still does.”The airbrush never touches the canvas,” she said. “You can make it in focus or out of focus really easily.”

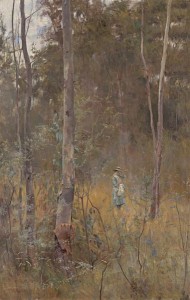

Lost, by Frederick McCubbin, from the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria

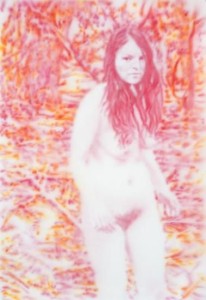

Having interviewed Lowry at the Archibald, I went home and dug out my notes from our interview when she won the 2008 Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, then being held at the State Library of NSW. Lowry’s winning painting was a nude self portrait in the Belanglo State Forest, scene of Ivan Milat’s chilling activities. It was a pretty brave painting, considering the ghastliness of the Belanglo crimes.

Lowry’s then dealer, Barry Keldoulis, told me that Lowry was “reclaiming the territory in the Belanglo forest”.

“She paints a lot of spaces where there’s been evil done. As a child she went to Bondi Public School, and came out and walked through the laneway and every street sign had a poster saying ‘have you seen this girl?’, and it was Samantha Knight, and her homely familiar streets were immediately imbued with fear and paranoia.”

In my 2008 notes, Lowry said her nakedness in the painting revealed a loss of innocence.

What I assume you shall assume, Fiona Lowry; winner of the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize 2008

“The setting is Belanglo, but it’s not specifically talking about what happened in Belanglo,” she said.

“It’s in general the malevolence of the landscape that has been explored since Frederick McCubbin painted his Lost painting. That’s a really interesting painting because there was this big fear of children wandering off into the bush in that time. So I think the landscape has always held that sort of element to it.

“I’d like in my work to play with those ideas (how evil events taint the landscape), and how you can bring these things together and make a new story out of those myths.”

Fast-forwarding to the annual Archibald Lunch at the Sofitel this month (August 2014), after the prize announcement, Lowry was on the stage with half a dozen other finalists and their subjects. Beside Lowry on stage, ready to take the audience’s questions, sat Penelope Seidler.

“We ended up in the gully at the back of the house,” Lowry said. “Penelope looked up at the house. It’s that moment that resonated with me. She’s reflecting on the space there, I guess, and that’s what that moment is.”

Penelope Seidler added to the story. “I remember it well, the moment Fiona is talking about,” she said. “I looked back and I think I said, ‘oh, I haven’t been down here for a long time’, and there’s a photo Max Dupain took in 1967 of me standing in more or less the same situation and I was thinking about that and the fact it was 46, 47 years ago and in a way nothing had changed. I was lost for a moment. It’s absolutely true.”

Penelope Seidler paid Lowry a lovely compliment. “I was lucky to be picked by her because I knew she was a good artist.”

Seidler even revealed she had bought the Lowry portrait. “I thought, ‘do I want anyone else to own it?’ So I bought it,” she said. “I don’t fancy the idea of having it hanging where I can see it all the time, but I’m sure I can find a nice home for it.”

Lowry said she had first seen Seidler at a gallery opening six years earlier.

“I was really captivated by her and felt her presence in the room, and I decided then that she was somebody I would like to make a painting about. Not even focusing on the Archibald.”

Fiona discussed her spray-gun technique, saying she began using it about 10 years ago after trying, and dismissing, spray cans. “The air brush allows fine movement and the ability to go in and out of focus,” she said.

Elizabeth Fortescue, August 25, 2014, Sydney