Unveiled: Biennale of Sydney 2012

Today [February 29, 2012] I attended the official unveiling of the program for the Biennale of Sydney 2012 at the Art Gallery of NSW. It left me with the feeling that this could be a Biennale that speaks softly. It won’t yell or have a tantrum. It won’t try to attract your attention with empty provocation.

Today [February 29, 2012] I attended the official unveiling of the program for the Biennale of Sydney 2012 at the Art Gallery of NSW. It left me with the feeling that this could be a Biennale that speaks softly. It won’t yell or have a tantrum. It won’t try to attract your attention with empty provocation.

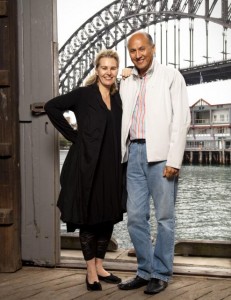

The two artistic directors are Gerald McMaster and Catherine de Zegher. McMaster spoke at length about the artists and about the Biennale theme, which is All Our Relations. His collaborator de Zegher was attending to a family matter in Belgium.

So here are the bare facts as outlined by McMaster:

* More than 100 artists from around the world will exhibit

* The main venues will be the Art Gallery of NSW, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Pier 2/3 at Walsh Bay, and Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour

* CarriageWorks will be a “presenting partner”, hosting the premiere of some new dance works

Gerald McMaster said the works to be on show would “delight our senses”, rather than being “critical”.

“Throughout the Biennale, audiences should begin to empathise in various ways where they will engage,” he said. “These engagements will move us much closer to bringing about change in our world, in much more concrete ways, where we begin to understand that indeed we are all connected. For some of you who do know this phrase [All Our Relations] it’s been inspired by a number of indigenous peoples around the world who at the beginning of their invocation usually say ‘to all our relations’. Basically it talks about how we are interconnected. So, inspired by this, we titled the exhibition. Throughout the life of the exhibition we hope that audiences will make such connections… and ultimately be much more aware of our interconnections and what this world is about.”

Works mentioned by McMaster at the press conference included:

City of Ghost, by Nipan Oranniwesner, from Thailand : “A composite aerial view of different international cities. It’s laid out on the gallery floor, and there are composite cut-outs and the artist takes baby powder and gently lays it over the top. This idea almost suggests the way that cities have achieved an unidentifiable sameness. Fortunately Sydney still has its own distinct identity.”

Do you remember when? by Postcommodity: “a work that was previously shown in Arizona. Connecting the earth and sky in an axis mundi. It will cut a hole in the gallery floor. I think it is a first since the beginning the building. Normally architects do that. In this case the artists will be doing that. We will be exposing the earth beneath the floor.” This will happen in Yiribana, downstairs in the AGNSW. “Postcommodity describes this hole, this portal as the point of transformation between worlds from which emerges two different discourses, … a relationship between indigenous and western world views, and a discussion about sustainability”.

Park Young-Suk and Yeesukyung: “Youngsuk is one of Korea’s national treasures who has devoted her entire career to perfecting the classic moon jar. They are particularly challenging to make, with the upper torso usually much fuller than the lower half, and the rim is usually wider than the base, making it extremely vulnerable to collapsing in the kiln. So from time to time she will see what she calls obvious failures. Yeesukyung’s work … takes pottery shards and recombines them into some very interesting forms, almost Baroque-like sculptures. The moon jar project brings the two artists together.” A film which documents the collaboration will also be played.

Nyapanyapa Yunupingu: “She will do a light series called Light Paintings. She took 110 drawings she did on acetate using a light pen and these clear acetates have been used as a slow dissolve. She is one of seven indigenous Australian artists in the exhibition. [There are 19 Australian artists in total in the Biennale].

Pinaree Sanpitak: Anything Can Break. “One of Thailand’s few internationally recognised female artists. Made up of hundreds of Origami cubes and glass clouds suspended from the ceiling, illuminated with fibre optics. They are lined with motion censors. They will trigger music and response to the audience’s movements.

Tiffany Singh, Knock on the sky listen to the sound: “It’s from a Buddhist proverb she heard while travelling into the Himalayas in her pilgrimage to a Tibetan monastery.” Wind chimes are meant to be good luck. Audiences will take the wind chimes from the space, take them home, perhaps decorate them, then be asked to bring them to Cockatoo Island where they will be displayed in some of the island’s trees.

Khadija Baker: On the ferry to Cockatoo Island, the 15 minute ride will be enlivened by performative pieces by the artist Khadija Baker, a Kurd by birth who lives in Montreal. People pick up one of her very long plaits and listen to a story of her commnity back in the Kurd region. “In doing so, in listening – as we’re hoping with many works in the Biennale – you begin to empathise with the artist, in this case almost becoming one wth the other as we now engage with her and actually listen to a strand of her hair.”

As you are nearing Cockatoo Island, you may be able to see fog emanating from it. “This is the work of Fujiko Nakaya [her work was installed 1978 at the NGA and she was in the 1976 Sydney Biennale. Her sculpture will cascade down from the top of a hill into the chasm between the rock and the turbine hall.]

In the dog-leg tunnel will be a work by Dutch artist Damien Roosegaarde. “Roosegaarde is one of the leading interactive landscape artists today. By touching, by singing, by dancing, the piece Dune will interact with you. It will play with you. Find an opportunity to get along and see what it does.”

Jonathon Jones presents a midden made from oyster shells and English teacups. Also his fluorescent tubes, which is inspired by his pet eels. “He has a large aquarium and every day he delights in their actions. And so he was inspired to do this piece.”

McMaster concluded by saying All Our Relations is “a direct response to the state of the world”.

“Please take the time to understand how the artists make us understand and be aware of our emotional responses, how they provoke us to ask new questions, and how they make us see the world around us much differently,” he said.

Elizabeth Fortescue, April 1, 2012

| Print article | This entry was posted by Elizabeth Fortescue on April 1, 2012 at 9:28 pm, and is filed under News. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. You can leave a response or trackback from your own site. |