Archive for October 11, 2010

Stephen Dupont talks to ArtWriter about his forthcoming exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography

Oct 11th

Australian photographer Stephen Dupont is putting the finishing touches to his next exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography, to go on show between Friday 15 October – Saturday 20 November 2010. The show is titled Afghanistan: the Perils of Freedom 1993-2009.

Last week, I interviewed Stephen in his Mascot studio so that I could write an article about him for the Daily Telegraph. The story appeared today (October 11, 2010).

However, given the importance and interest of Stephen and his work, I thought that many people would enjoy reading the full text of our interview as it was recorded and transcribed by me. Here it is. I have edited it lightly:

ArtWriter: Can you talk us through the ACP exhibition and what it will cover?

Stephen Dupont: [It will be] a very much edited body of work from 15 years of coverage. It ranges from 1993 through to 2009. Essentially it’s a retrospective of work from that period. I’ve been incredibly selective. In order to do the story justice I’ve decided to do a lot of installation kind of work. So for instance these are small mock-ups but the exhibition will have entire book dummies right across the walls, almost like wallpaper. These are the original Moleskin pages. They’re going to be huge. So people will see the whole dummy that I’ve made. That’s another booked called Stoned in Kabul. So people can read it, see the work, and it also involves my handmade books which is a big part of what I do. The whole exhibition is quite ambitious; it’s not like anything I’ve ever done before. It’s going to be incredibly busy. It’s not about cramming everything in. It’s really about giving the work room to breathe, and also tell the story, because it goes beyond the photography, it goes to the history and politics and everything else about what’s been going on about Afghanistan over the last 15 years. So it’s also these elements are shown, and also in an artistic sense they’ll look really interesting as well. My diaries will be in there as well. It opens up a whole other message, I suppose.

So you’ve got that element, then you’ve got a suicide bombing. This is probably easier to explain by running through the gallery. So when you enter there’s going to be a huge mural of [Ahmed Shah] Massoud, then the exhibition starts with the civil war, 1993-1998, these are all single photographs, then it moves into Massoud who was the former leader of the Northern Alliance. He was assassinated two days before September 11 and he was Afghanistan’s real hope of peace. And he’s now the national hero. I spent a lot of time with Massoud. He’s an important part of my work. This is all in chronological order. Then you go into the war on terror, which is 2001 to 2009. So that’s basically when the Americans and NATO forces arrived. Then you get to the huge mural called Taliban Burning. You might remember there was a photograph and also video footage that I’d taken of American soldiers burning the bodies of dead Taliban which started controversy around the world. It’s the size of a wall, basically. It’s a huge print. And it’s meant to shock people. It’s an intimidation of what took place. And there’ll be an excerpt from my diary about what happened. Each section has an excerpt of my diaries, so it’s like a message for people to read about something that happened at that particular time that I reflect on.

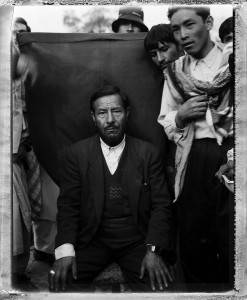

This room here is called Axe Me Biggie. It’s a series of portraits I made in 2006 of anonymous, mostly men made on the streets of Kabul. It was shot in an afternoon and these are life-size mural portraits taken on Polaroid. They were taken with a traditional Afghan photographer’s backdrop which is all crumbly and decrepit. I basically used that outdoor studio kind of feel to make these portraits.

Then you go into this installation room. So you’ve got Stoned in Kabul, this book dummy, basically taking up that whole wall. It’s about heroin addiction. This project is about two brothers addicted to heroin. And it’s a window into the whole narcotics situation in Afghanistan, but mainly from the point of view of addiction and how local people have suffered from the blow-back of Afghanistan being the world’s biggest provider of heroin and how it’s affecting the local population.

Then you’ve got Why am I a Marine?, my most recent work. This was a series of portraits I’d done on one American Marine Platoon in Helmand province. I photographed them and I put a question, why am I a Marine? to everyone in my journal, and they all wrote a personal testimony about why they became a Marine.

Then you’ve got Why am I a Marine?, my most recent work. This was a series of portraits I’d done on one American Marine Platoon in Helmand province. I photographed them and I put a question, why am I a Marine? to everyone in my journal, and they all wrote a personal testimony about why they became a Marine.

Then the suicide bombing is here. I was in this bombing incident in 2008 where I escaped this suicide bombing and photographed the aftermath. So there’s 60 pictures almost like a contact sheet, before and after the bombing. That takes up that whole wall. It’s very graphic, as you can imagine it is.

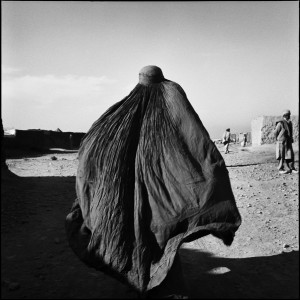

The last section is Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, which is a reflection on photographs that are personal and poetic and so forth that I think really represent Afghanistan yesterday, today and tomorrow and that’s going to be a grid of bout 15 photographs. Then you’ve got contact sheets on each of these walls that are going to be plastered down the side. You will not be able to get away from imagery. It’s going to be a flood of pictures. And that’s the intention. It’s an incredibly busy show and I’m hoping that people will take time to really take that journey and take in my journey and the journey of the war in Afghanistan.

It will be interesting to see if I pull it off.

How did you get involved with Afghanistan in the first instance?

How did you get involved with Afghanistan in the first instance?

I had been reading books and researching, and the romanticism of Afghanistan and the “great game” and the spying through the British and the Russians from books like Peter Hopkirk had written about it, and Rudyard Kipling, Kim, so there was this romantic notion of Afghanistan, this wild frontier and then the amazing imagery of Mujahideen fighting the Russians so it was incredibly appealing to me as a photographer back in 1992-93 when I’d just moved to London. Then I read a report about … the civil war in Tajikistan had broken out and 100,000 refugees had fled, the Russians were starting to pull out of Central Asia but they were still very much in control of Tajikistan and when the civil war broke out the Russians were shotting the refugees as they tried to swim across the river into Afghanistan. So this massacre took place. And the refugees who made it into Afghanistan ended up in these squalid camps in minus 20 degrees Celsius conditions in the middle of winter. And I read this story and I just thought this is f…ing unbelievable, the fact that you’ve got to flee a civil war and you go to Afghanistan? It’s like Afghanistan has got a civil war erupting itself and it’s worse than the place you’ve just come from. How f…ed is that? As a refugee, that your only salvation is Afghanistan? I just thought this is the most absurd situation, and horrific situation. So I went and covered that story for my agency and papers and people in London, and while I was there covering the refugee story I met some doctors from Medecins Sans Frontieres in Mazar in the north, and they were saying to me you should go to Kabul because the whole city is under rocket attack and there are tens of thousands of people being killed and there’s only one journalist there, and it was just like no one was covering it back then. So I took this road journey with a doctor. I disguised myself as a doctor to get through all the check points, so I hid my cameras in the back of the car. I got looked after by MSF [Medecins Sans Frontieres] in Kabul. We made it into Kabul under rocket attack. The whole city was just being bombarded every day just continuously from various different factions fighting over the city. So it was this incredibly intense and insane situation, running around the streets of Kabul trying to photograph it and trying not to get blown up. I decided to focus on MSF and what they were doing. It was only like three or four international doctors that were there. Not many other aid organisations were there, it was just too dangerous. So this hospital that they were running, which was the main hospital in Kabul, was flooded with the wounded and dead from the rocket attacks. So I did this essay around what MSF were doing and the situation around how civilians were trying to survive in this Grozny-like city which was just completely destroyed. That was my introduction. I went back to London and got itchy feet and thought I’d better go back again. You really get caught up in the story. I really felt for the people. I felt it was important to cover this story because no one else was really doing it and it was an incredibly important story for the world to know about. If anything, I thought I’d get my pictures published, but it would be this body of work that I would hope that one day that it would be a template of history of the people of Afghanistan. I had no idea that 2001 would come along and the whole world would focus on Afghanistan. I’d already been going there for eight years. When that happened it was almost another chapter.

When that happened in 2001 I couldn’t stop, so the journey never ended in a way, although now I’m starting to put everything together because you need to put closure on things and this for me is the closure on putting this show together and publishing a book.

I’ve kept diaries right through. I do different things for different bodies of work. I made these books. [Stephen showed me a couple of his artist’s books, all printed by him and put together by a bookbinder. They have a kind of Bauhaus aesthetic, and are gorgeous to look at and handle.]

The exhibition is really about showing this kind of thing in a gallery context, as well as traditional prints. They’re also looking at getting a table for objects so I can lay out these books.

It’s a lifetime’s work, basically, and I’ve only got a certain space to fit it in.

Where were you on 9/11?

I was about to go and meet Massoud. It was extraordinary because I’d already got my ticket and visa, I had planned to go and on another trip with Massoud and September 9 he’s blown up. I was in shock; it was shocking. And of course my gut feeling was that I should still go because this is going to have huge repercussions on the civil war andwhat was happening with the Taliban and so forth. I was still on my way to go there, and two days later September 11. I was sitting in my lounge room and watching it live, in Sydney. I knew that this was somehow connected and that there would be some huge repercussions from that as well. Whatever happened I knew I had to be in Afghanistan and I ended up in the first stream of journalists trying to get into northern Afghanistan and I ended up going in for about six weeks on that trip as the Americans started bombing and the whole thing kicked off. I went in with the Northern Alliance, as most people were doing.

I can’t even imagine how you live? Where you sleep?

Anywhere you can. Basically you’re in bandit country and you just hope you don’t get rolled.

You live on your wits?

You live on your wits, but often you’re with other people. It’s not often I was alone. I would usually have a couple of other journalists with me. Safety in numbers. It tends to be OK. I’ve never, touch wood, had any huge issues. Not from the travelling aspect of it. I even walked out, just myself and a couple of Afghan guards, out into Pakistan. That was like a week on foot and horseback because it was the quickest way out. Not the safest but the quickest. Otherwise I would have been stuck there with 1000 other journalists trying to get out. It was a really bad situation where the whole world’s media had flooded into Afghanistan and then everyone wanted to get out again. They were all sleeping at a place in the Panjshir where a helicopter would come and retrieve a few people at a time. I remember going there and looking at all these dejected journalists, really depressed, and some had been waiting for, like, four or five days, and there was no food or running water. I had already arranged to meet an Afghan commander in the north and pay some guards to take my out into Pakistan. It was an amazing journey.

This exhibition is about people and Afghanistan, but it definitely has a lot to do with my journey and how I reflect and what I’ve seen. It’s very personal.

How does this change you as a person, being a witness to human misery?

My parents were social workers. I grew up around a lot of displacement in a way. Maybe that had something to do with my attraction to thrid world misery ro something. I had a fairly normal upbringing I suppose. Photography came first then the inspiration for doing social documentary and news reporting was second. I very much started as a news photographer, freelance, running around the world chasing stories. I’ve developed much more into a more personal vision and opening up my diaries and trying to say something more personal.

Is this the first time you’ve opened up your diaries?

Yes, in a gallery sense.

What other conflicts have you covered as a photographer?

I covered the Angolan civil war in ’93, then Zaire and Somalia. Sri Lanka civil war, the Middle East, Rwanda and the genocide. A lot in Africa. Africa and Central Asia were the two main areas I focused on.

You spoke before of closure. Do you see this exhibition as the end of your work in Afghanistan?

No. I’m planning to go back next year and shoot a documentary film. It would be just another chapter of my life. I’m hoping to do a film about the Marines.

Do you have friends in Afghanistan?

Definitely. I have Afghan friends and contacts that I’ve seen on different trips, and expats. People come and go. Sadly a lot of people die. A lot of people I know have died or been killed because of the war. It’s a very transient place, and constantly changing. Constant struggle of dealing with the horrors of war. These people have had nothing but war, and they still have war. People are still suffering and still dying. Civilians. For me this is a dedication to the people of Afghanistan. This is my thanks for the access and the friends and the safety and camaraderie.

Are the Afghans good people?

Amazing people. Incredibly honest and resilient. So diverse and culturally wonderful and intelligent. So much history. One of the big things that attracted me was to do with their history and culture.

Because of our government’s f…ed up attitude towards refugees and asylum seekers, I’m quite interested in somehow exposing something that exposes the struggle that asylum seekers have in this country, and a lot of those asylum seekers Afghan or Hazara people so when they get back to Afghanistan their future is nil. If they’re not killed, they’re persecuted. So for me there’s a powerful message in trying to highlight that situation.

That was the end of the recording.

Afterwards, Stephen told me he shoots almost exclusively on film, not on digital.

“I guess I’m a bit old school in that way,” he said. “If I have to shoot colour, I sway towards digital. But I normally shoot black and white.”

He uses Leicas, Polaroids (yes, Polaroids) and Rolleis.

Elizabeth Fortescue, October 11, 2010