Archive for December, 2012

Song Dong and Waste Not: the artist and his work

Dec 29th

A few weeks ago, Chinese artist Song Dong arrived in Sydney prior to installing his Waste Not project in Carriageworks, Eveleigh, as part of the Sydney Festival 2013. He was also preparing for his wider exhibition at the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in Sydney. I met the artist shortly after he arrived at Carriageworks, and had many questions concerning what I thought was a fascinating project.

A few weeks ago, Chinese artist Song Dong arrived in Sydney prior to installing his Waste Not project in Carriageworks, Eveleigh, as part of the Sydney Festival 2013. He was also preparing for his wider exhibition at the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in Sydney. I met the artist shortly after he arrived at Carriageworks, and had many questions concerning what I thought was a fascinating project.

Song Dong turned out to be a quiet and self-effacing person. But he was also engaging, and very keen to discuss the intricacies of the project.

A short preamble: Waste Not (or Wu Jin Qi Yong in Chinese) is a remarkable artwork which constitutes an actual bedroom and living area of his mother’s tiny Beijing home as well as more than 10,000 individual domestic objects which she kept, some of them for up to 50 years.

The modest little home still exists, minus the small section which was demolished because it failed to reach safety standards. The house is in Banshang Hutong, a tiny street where traditional daily life still bustles on virtually in the shadow of “new” Beijing’s high-rises.

Waste Not includes chairs and tables (some broken), fabrics, two old beds, wardrobes full of second hand clothes, hundreds of kitchen utensils from mis-matched sets, hundreds of old shoes, toys, electrical wires, enamel basins, plastic buckets, string, old magazines, lamps, clocks, telephones, record players, empty toothpaste tubes, bottles, bottle caps, fast food containers, hard soap bars, shopping bags, moon cake boxes, tea boxes, yarn, radiators, blankets, bird cages, old television sets.

Song Dong’s mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, saved all these things from the 1950s to 2005. To understand why, you need to know her story.

Zhao Xiangyuan was born in 1938 in Taoyuan, Hunan province into a prosperous family. But in 1953, her father was declared a spy. He was arrested and jailed. The family’s circumstances changed dramatically.

Zhao Xiangyuan and her mother struggled. They lived in a tiny home in hardship and poverty. Zhao Xiangyuan sewed buttonholes and glued paper bags for department stores.

Zhao Xiangyuan married, and her son Song Dong was born in 1966. Life was hard, and the young family lived in a single room. Zhao Xiangyuan began to hoard items like soap, which was rationed.

In 2002, Zhao Xiangyuan’s husband Shiping died suddenly. After that, she couldn’t bear to part with objects which reminded her of her past domestic life.

The life of privation which gave rise to the Chinese proverb “waste not” affected an entire generation, but is little understood by the young people of modern China, for whom consumerism and commerce are a way of life.

After Zhao Xiangyuan suffered a nervous breakdown and refused to part with any of her hoarded objects, Song Dong devised a way of helping her out of her silent grief. He decided he would create an artwork in which his mother would be the true artist and he would be her assistant. That work was Waste Not. He would rebuild a corner of his mother’s home and offer her the chance to sort through all her belongings. He called it “organising her memories”. As she sorted, she discussed all the items and their histories. Finally, the sorted items were exhibited for the first time in 2005 in Beijing.

At that time, Song Dong’s mother said to him: “You see that keeping [all the objects] was useful!”

When the work was put on show, Zhao Xiangyuan was on hand to discuss her life with visitors. The older ones among them would have identified completely with her frugality, having also lived through hard years when no one ever threw anything away. Anything, they would say, could come in useful some day. Discussing all these things brought Zhao Xiangyuan out of her shell. It had exactly the effect for which Song Dong had hoped.

The artwork became a true family affair. Song Dong’s sister Song Hui is also involved, and was there the day I interviewed her brother at Carriageworks. She is the project archivist.

Song Dong’s wife Yin Xiuzhen (an artist) and their daughter Song Errui (aged 10) were due to arrive the following week to work on the installation of the work. Song Dong told me that he talks to his daughter about the objects as they arrange them together, so she learns about her family history that way.

Zhao Xiangyuan, sadly, is not able to help with the Sydney presentation of the project. She died in January 2009. Her family, however, is carrying on without her. I have read an interview in which Song Dong declares that his mother was the one who deserved the prize which the work won at the Gwangju Biennale, because “she has used her entire life to create this work”.

Waste Not has already been seen in New York, Korea, Germany, England and Berlin.

Here is my interview with Song Dong, carried out on December 13, 2012.

Song Dong: This is a part of our home. We have six rooms but this is two rooms. Our family moved many places. In China we can’t have our real own house. This is a very traditional (house).

He said the house would be more than a century old and many families would have inhabited it.

We rented the house. Every house belong to the government. Now we can buy the home. But only the house, the land is the government’s. My mother also lived inside, for two or three years. Because the government said too old, very dangerous. You should take down. So I built the new house there but my mother said don’t throw away anything. I said where I can put? She said you can use them to build a new house because the wood is still good.

Since 2002 my father suddenly passed away. My mother silent. Just cry. Don’t talk with other people. I can’t do. I can’t help her. So I send my mother to the south of China with my sister while we organised her home. We think she happy with organised home but she was really angry. Why do you throw my things away? The whole night I can’t sleep. I asked her why [did she get angry]. She said your father is gone. I afraid of empty room. I need the object to fill and cover memory so I can feel your father still there. That really touched me. I thought I will give my mother a job. Let her organise things. I said we will keep all of them. The job is to put the same thing together. For example the shoes. I want her to know how many shoes you have. How many things you have.

His mother had misgivings that people would think she was messy, but her son encouraged her.

I said when we show this work, I will be famous. Because before I did a lot of work with my father. It will be shown in 4A. All the work is working with my family. Because they can do everything for me.

Now I am really sad to throw away. [He wishes he hadn’t thrown away a lot of old used tea-leaves, which his mother used to keep in case she wanted to stuff a pillow with them].

That’s the old generation. But the young generation they throw away anything. They just want to use everything now. Mobile phone. The whole society wastes a lot. It’s not a good thing for our life. This project shows people to think what can we use again.

His mother died in 2009.

This project is not a still show. It’s a develop show. When my mother alive I work with her each time doing the exhibition and she note down a lot of the story of each [object]. We make the archive.

In the beginning it was really hard for my family. I cry every day.

In that work, my mother and father never pass away. I think they are living in art.

Each time [the work is installed] is different because I will reshape the space. [There are parts for the parents, the grandparents and his own children.]

My wife also artist. She help us to do the image archive. One by one every object will take the photo. Maybe in the future we will make a website of it.

I looked up about the Beijing hutongs on-line, and found they are the historic heart of Beijing. They are higgledy piggledy little lanes and alleys, full of old charm. From the sky, they are an unbroken plateau of tiny rooftops. They are under threat of redevelopment, but those who fight for the hutongs are very passionate about them, describing them as the culture of Beijing itself.

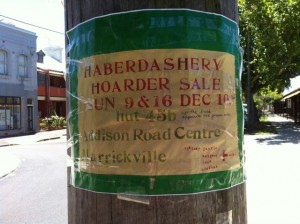

After my interview with Song Dong, I noticed this poster on a pole outside Carriageworks. The story continues.

Elizabeth Fortescue, December 29, 2012