Archive for April, 2014

Bill Brown: Sydney artist talks to Artwriter before his retrospective exhibition at S. H. Ervin Gallery

Apr 27th

Bill Brown is a fascinating character and a great artist from the inner Sydney suburb of Newtown. Brown’s retrospective exhibition, Bill Brown: Wanderlust, is running until June 1 at the S. H. Ervin Gallery at Observatory Hill, The Rocks.

The first time I heard about Bill Brown was when I interviewed Lucy Culliton many years ago, when she was having one of her early shows at the then Ray Hughes Gallery (now the Hughes Gallery).

I asked Lucy about some of her most influential or inspiring teachers. Lucy immediately mentioned Bill Brown, who taught her at the National Art School in Sydney’s Darlinghurst.

I tucked the name away in my mind for many years, and when I heard that Bill Brown was to be the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the S. H. Ervin, I knew I just had to meet him. I lined up an interview with Brown at his Newtown studio, and wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph. I realised the extent of Brown’s influence on the Australian art world when I posted on Facebook that I was about to interview the artist. I was surprised by how many comments the post attracted. I’ve reproduced some of them below, along with Lucy Culliton’s comments when I rang to let her know I was about to interview her old teacher.

I’m pleased to be able to run the full text of my interview with Brown here on artwriter.com.au

Brown began by saying that he learned “form” as a student, which gave him the power to introduce whatever he wanted into his art works.

Brown: When I was 15 I left school and worked for four years in advertising. J Walter Thompson. It was a cauldron of creativity and everything was done by hand. I would see the layout people generate form and variation. (This is important to Brown. He was quite vocal about one version of a work leading to another and another. Like Matisse’s women in those drawings where he gradually refines his vision down to its essence.)

Brown said his teacher at the NAS had been Wallace Thornton.

“(Wallace Thornton taught that) every point of arrival has to be seen as a point of departure. You were never allowed to hang on. You had to keep moving. It was the 1960s and it was full of freedom and evolution and that’s how my paintings happen. In this exhibition you will see that even though I work on paintings individually, like I’ll start a painting without too tight a concept and with no clear outcome in mind, and the painting will evolve. I put something out there and it’s just to consider while the imagination takes over. The imagination is not like a solid block of something in your head that’s full of stuff. It’s a response.”

Brown said teaching was “nurturing, not lecturing”.

“I got every good at it in the end. Teaching became a great learning thing for me because I had to work out what I wanted people to understand.”

Brown said painting is not about “frozen moments”. “It’s always about creating and about moving through your ideas that you have evolved and grown as much as the painting,” he said. “So I am me, but I am always shifting.

“Once I understood that the nature of painting is an illusion, the more realistically you make a painting the bigger the lie. That’s been the basis of my understanding. I couldn’t believe in capturing something so I had to create something.

“At the same time I understood there was depth of form, colour, harmony etc and that became the language with which I make paintings. It’s like poetry in a way. These things are total fiction but the best of them is poetry.”

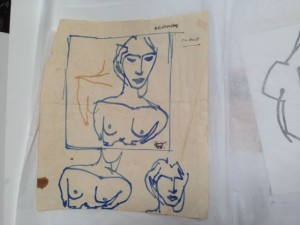

We looked through some of Brown’s sketch books, many of which date back years. “My drawings are like money in the bank. a bank of drawings,” he said. “I will come in (to the studio) and allow myself to be struck by something. I see something and say ok I’ll take you on. I keep on evolving and I work across a number of paintings.”

I asked him about the numerous New Guinean masks that are hung on his studio walls, and which pop up in many of his paintings. “I have included then in my life,” he said. “They are like silent witnesses that are just around me. I have always tried to just work with what’s given. Life is a given thing and if you start idealizing about it you probably miss some interesting things.”

Brown spoke about putting as much effort into the acorn as the tree. “The difference between the two is the imaginative journey,” he said.

He pointed to one of his “Ship of Fools” paintings and we talked about the hand reaching out of the water on the lower right. “To me it became the hand of God, or it could be me or somebody being lost overboard,” Brown said. “The enigma of it all. I quite like that. It’s a consequence of not having a fixed idea of outcomes.”

You might expect that Brown has been an avid traveller, given the title of his retrospective exhibition. But this is not the case.

“I travel in my mind. I’m a very poor traveller,” he said.

We spoke about how he left advertising because he was not interested in the idea of materialism and selling things. He brought his ideals into the National Art School.

“I could never aim anybody at a career because I’m a Romantic and a bit of a purist, I suppose,” he said.

“One of my little sayings is I have not confused the business of art with the art of business.”

Lucy Culliton: “He was one of my painting teachers. He was by far my best. He’s so generous. And I used to ride horses in the morning so I was always early and I would get I there before class. He was an early riser so he would come in early and I would make him a cup of tea and we would talk about my paintings. It was a lovely routine. After art school we kept good contact. I did hog bill. I didn’t share him. When you are hungry to learn, you pick someone who gets what you’re doing.”

Facebook comments:

“We all clambered over each other to get into his drawing class.” Harrie Fasher.

“I used to bring my dog Wally to art school every day and he had his name on Bill’s roll book.” Kerrie Lester.

“Bill Brown, with his warm spirit and unassuming manner, coupled with a wealth of knowledge seldom encountered, made a lasting impact on many of our lives. Many Bill-isms still direct me both in my work and in my own classroom.” Tanya Rose Fielding.

Elizabeth Fortescue, April 27, 2014, Sydney, Australia