Elizabeth Fortescue

Elizabeth Fortescue is the visual arts writer for the Daily Telegraph, Sydney, and Australian correspondent for The Art Newspaper, London

Homepage: http://www.artwriter.com.au

Posts by Elizabeth Fortescue

At Home in Bibbenluke with Lucy Culliton

May 10th

Lucy Culliton is an Australian artist who has built a large and stuck-fast following thanks to the steady stream of heartfelt, individualistic, quirky and sheerly gorgeous paintings that she has been producing since graduating from the National Art School in 1996.

Lucy Culliton is an Australian artist who has built a large and stuck-fast following thanks to the steady stream of heartfelt, individualistic, quirky and sheerly gorgeous paintings that she has been producing since graduating from the National Art School in 1996.

I first met Lucy when she had just left her horse-painting period behind and was entering on a new obsession, this time with iced cakes.

Lucy’s cake paintings dripped with slickly shining icing, they oozed with whipped cream, their decorations stood out so that you could almost pluck them off and pop them in your mouth. At that time, Lucy was living in Surry Hills in the inner suburbs of Sydney, and she bought her “models” from the local cake shop. They were so full of preservative they took ages to go off.

Since the cake phase, Lucy has moved on through her hens and roosters stage, her particularly robust cactus phase, her rusty shed-stuff stage, her country show with decorated Arrowroot biscuits and knitted toy stage, and so on.

Her present preoccupation is with painting her beautiful new home just out of Bibbenluke village in the rural Monaro district of southern NSW.

It is Bibbenluke Lodge, as her home is called, which was the subject of Lucy’s recent exhibition, titled Home, at Ray Hughes Gallery [April 2-28, 2011].

Throughout the process of becoming a very well-known artist, Lucy has never changed. Her sole focus has remained on her work. She has always surrounded herself with animals of all shapes and sizes, from the dogs that are always around her feet, to the rat and the rabbit which she kept at her Surry Hills home when she was living there, to the pet lambs she now has roaming around her big country garden.

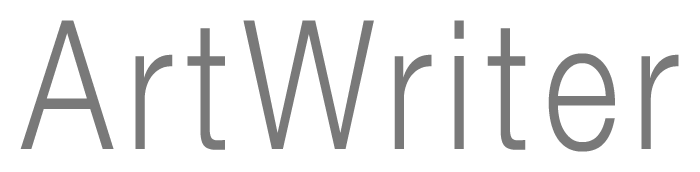

In the exhibition, Home, Lucy was in top form, painting herself into the interior landscape of Bibbenluke Lodge, the house that was built in the 1930s and subsequently pressed into a range of uses including that of a fishing lodge.

Not that Lucy literally paints herself into her pictures of Bibbenluke. But her spirit is there. She paints her dogs sprawled on the rumpled bed, her poddy lambs with their legs tucked up underneath them on her living room chair. There’s a painting called The Good Room – ‘Reno’, with a Tasmanian tourist tablecloth on the table and a big painting of a skewbald horse on the wall, evidently one of Lucy’s current or former steeds. She current has five. There’s Lucy’s clothes rack in front of the gas fire while a couple of dogs curl luxuriously in the armchairs. Only in one painting, Other Bathroom, do we see the artist herself. She is right at the end of the picture, reflected in a bathroom cabinet mirror looking past the pedal bin, the toilet, the bath and basin, and the oil heater. Lucy shows herself at her easel, blissful, loving every stroke of her new home and her new life.

“I love this place [Bibbenluke Lodge],” Lucy writes in the introduction to the Home catalogue. “In the morning I wake up excited about the day ahead … all my projects that I have planned. They are alays packed into a very full day which starts with a pot of tea, then I’m out greeting and feeding my ‘family’ of animals. After my breakfast is painting. Painting is my job; I love my job”

Later in the day she will ride a horse, tend to her large garden, do some craft. Through Lucy’s paintings, the rest of us can be there alongside all this happy and fulfilling activity.

I interviewed Lucy on April 14, 2011, for a story I wrote for the Daily Telegraph. The story was about the exhibition, Home. I reproduce it here, with light editing.

How long has it taken you to make the work for this exhibition?

This current show is about a year’s work. [It’s been] 18 months since the last show but it took me six months to figure out what I was painting next. I painted different paintings of different subjects but it took a while to work out I was going to paint my interior, that that would be my next direction. After a show finishes, like right now, I go out, I paint landscape, I paint a bit of still life, I get someone to sit for me, and then I decide, when it’s ready, what will be my next theme. You’ve got to think about it.

Did it come to you in a flash you’d like to do the interior of Bibbenluke Lodge for your show?

I have collections of things and I was thinking I would paint them, but I guess I wanted to include the garden so that sort of came out of that.

Some of the paintings in the exhibition have real lambs sitting on the furniture. Did you really have sheep in the house?

I did. They were poddy lambs. It was in the middle of winter; it was very cold. They both had nappies on. You can’t house train a lamb. They’ll wee on your lap while you’re watching telly.

Do you have to use special lamb nappies?

No, I was terrible, I had disposable nappies. The first nappy I started was the newborn nappy and Map, the bigger lamb, got into junior size nappies and I’d have to tape them around her middle because she got too big for them. [The lambs are Map and Marvel.] I now have Kenny Wayne and May Belle [new lambs].

What are poddy lambs?

They’re orphaned or rejected by their mothers, so they’re hand raised on the bottle. A grazier neighbour gives me his lambs.

What happens to them once they’re grown up?

They’re pets. They’re outside and they’re pets. And when I go for a walk, they all come with me.

They imprint on you?

Totally. Sheep are beautiful. I love sheep.

In the “dog room” painting you have a magpie inside the house. Did it come in as well?

Yes. The first two years I was here I had a baby magpie called Baby. He was free to come and go but he slept inside at night. He disappeared after a while but last winter I had another juvenile magpie that I rescued, it was drowned on the road, and I had him for two months. And that was him in the paintings. I didn’t want him too tame, so I fed him worms and cheese and dog food. I wanted him to go back out to the wild. [He did.]

And what about the ducks in the washing basket?

Yes, that was one duck, and then he got up and moved so I painted him again. That was a rejected duckling that I had in the house for a while.

How long have you lived at Bibbenluke now?

Three and a half years. Four in September. The community is very welcoming. I’ve made really good friends. And everyone’s interested in my painting and what I’m up to and I’ve got really nice support.

Sounds like you’ve found exactly the right spot.

I did.

How many dogs have you got?

Three. Birdie [Lucy’s parents’ dog] was visiting. The others are Bonnie [the Staffie], Earl [the greyhound] and Hephzibah [the Blue Heeler].

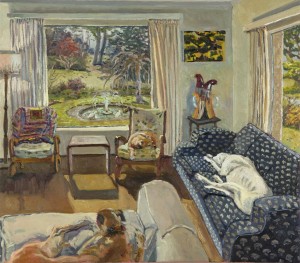

My favourite painting is the one of Earl in the bath or shower [see image at left]. How did that picture come about?

My favourite painting is the one of Earl in the bath or shower [see image at left]. How did that picture come about?

Well I wanted to paint my bathroom and I wanted somebody in the picture, so I put him in the bath and told him to stay. It has no water in it, but he just stood there, and I painted him, and then he got out.

He didn’t mind?

Well he looks pretty sheepy in the picture. He wasn’t happy. He thought he was going to get washed, but he didn’t.

[Sadly, Lucy’s nephew Reuben Culliton, 17-year-old son of Lucy’s artist sister Anna Culliton, had been killed in a car accident on March 12, just a few weeks before this interview. Lucy went on to speak of Reuben with great affection.]

I was training him to be … well, he used to prime all my boards and sand them just right. I got him well trained as an artist’s assistant.

What would you like to say about Reuben?

Well, he was a great musician and he had made a couple of fantastic short films at school which won awards. He was just friends with everyone. He was my assistant. He used to come down in his holidays and work for me in my garden and I’d pay him to ride horses, I’d pay him to prime canvases for me and sand them back and things.

It sounds like you guys were really close.

We were. When he was born, Anna and I and Boris [Reuben’s father] lived in a share house, so for the first year Reuben was a flat mate. So he’s my only experience of living with a baby. He felt like my borrowed child. You know how for population you replace yourself? I always thought, well, Anna [who has two other children] has replaced herself, Boris has replaced himself, so Reuben can be me.

Elizabeth Fortescue, May 10, 2011

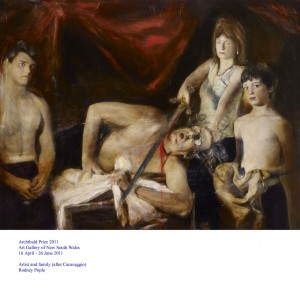

Backstage at the Archibald Prize: paper planes and steel-plate etchings

Apr 17th

When Ben Quilty won the Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW in Sydney yesterday [April 15, 2011], it was less than a decade since he had received his first real career boost – the receipt of the 2002 Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship. And Margaret Olley, one of the judges of that scholarship in 2002, was the very appropriate subject of Quilty’s Archibald winning portrait. Both artist and sitter were at the gallery when the $50,000 prize was announced.

When Ben Quilty won the Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW in Sydney yesterday [April 15, 2011], it was less than a decade since he had received his first real career boost – the receipt of the 2002 Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship. And Margaret Olley, one of the judges of that scholarship in 2002, was the very appropriate subject of Quilty’s Archibald winning portrait. Both artist and sitter were at the gallery when the $50,000 prize was announced.

Quilty’s two young children, Joe and Olivia, made paper planes from copies of the press release, their youth somehow showing how an art prize that is 90 years old is still going strong. I observed all this as the visual arts reporter for the Daily Telegraph.

I first met Ben Quilty many years ago when he was just starting to exhibit his work to the the beginnings of what would become acclaim. It must have been just after he won the Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship in 2002. Right back then, it was obvious he was a young man going places. And boy, could he paint.

I thought he would win the Archibald a few years ago when he entered a wonderful portrait of Beryl Whiteley, who established and endowed the travelling scholarship in her son’s name. It was a great painting of Beryl; so full of steely determination and the will to survive, no matter what. I saw the painting in Ben’s studio, which was then in Alexandria. Ben would miss out that year, although his portrait of Beryl Whiteley did make it to the finals. But this year he has stormed home with his wonderful evocation of that grande dame of Australian art, Margaret Olley.

There was a definite sense of history and the passage of time yesterday when Ben was announced as the winner of the 90th Archibald Prize. Margaret Olley, of course, was the subject of William Dobell’s 1948 Archibald Prize winning portrait. At that time, Olley was a young unknown, just about to leave for Europe for the first time and embark on what would become a long, sometimes bumpy and richly creative life.

Yesterday, there she was again, this time as a near legend, as well known for her own lifetime’s artistic output as she is for her remarkable philanthropy. Edmund Capon, director of the Art Gallery of NSW, told me yesterday that Olley’s gifts of local and international artworks to the AGNSW are in the vicinity of $8 million. Some of those gifts to the gallery were paintings by Quilty.

You can see what attracted Olley to Quilty’s painting in the first place, when she and AGNSW curator Barry Pearce were judging the 2002 travelling scholarship. There’s a love of the creaminess and viscosity of paint, a deftness of application, a daring to be different, and a dangerous edge to the subject matter. Sometimes Quilty has gone too far, however. Accepting the prize yesterday, he admitted that Olley hasn’t always liked what he’s chosen to paint. Quilty has specialised in painting the emblems of young Australian male angst – human skulls with cigarettes clamped in their jaws, or revving Toranas. Olley had visited his studio one day and, seeing his latest works there, had asked what he was doing. “Experimenting,” Ben had replied. “Well, stop experimenting,” Olley had told him, characteristically to the point.

In return, Ben had a nice story about Olley. “Recently I was amazed at how many new works she had on the go,” he said. “She said to me, ‘I’m like an old tree dying and setting forth flowers as fast at as it can, while it still can’.”

If Olley is urging Quilty to “celebrate life” rather than death, then she’s leading by example.

I finally got my interview with Ben after all the radio and televisions stations had done their live crosses. Here’s what he said:

Why Margaret Olley for the Archibald?

Because she has been such a long time mentor for me. She’s someone who seems to incongruous with my practice. Which I actually now like. Why not? You’re meant to be able to do whatever you want as an artist, and in the past I have felt very in a way very sort of controlled in my choices, just to continue to fit in with what is deemed contemporary. When she said that comment about the old tree, I thought “that’s amazing, what a human”. It was so powerful. She suffers from depression, and I would instantly link [depression with a] fear of death. But it’s not. She gets depression but she has the healthiest regard for her own mortality. And that’s what my work’s been all about. Especially young male mortality and what it means to be a young man.

She supported you all through your skulls and Toranas, but she didn’t really like them, did she?

No, no, no. She’s always said to me “you should make paintings about a celebration of life, rather than this dark, introspective paintings about male youth”. And I always stuck to my guns and said “well, Margaret that’s what I do, that’s what my experience is”. And I’m sure I will come to a different point in my life where I am celebrating my existence, but at the moment I’m mkaing paintings about my experience about young masculinity and I feel like they’re a part of society that is voiceless and they need to be heard, and I’m the person that can help that happen by talking about it. No one talks about that stuff, and it’s brutal and awful and a devastatingly difficult thing to live through as a young man. So Margaret understood that, but she also said “why can’t you talk about those things by celebrating life and showing that you’ve come through it?” So we’ve always had this discourse and a very healthy regard for each other’s point of view but also not entirely agreeing with each other, which is what it’s about. It’s about challenging each other. She was totally fine with me to keep doing it, she’d just pull me up every time I did and say stuff like that, “stop experimenting”.

You’ve started a series of portraits on Kylie [Ben’s wife, pictured left]. Is that a concession to Margaret?

You’ve started a series of portraits on Kylie [Ben’s wife, pictured left]. Is that a concession to Margaret?

No, that’s a concession to Kylie. In one show I had last year called Inhabit, that was a very dark show, very dark, and it was a very hard year for me for a number of reasons, personal reasons and stuff, and she [Kylie] said then “you live with these paintings, you’re in the studio all day every day, with these works, sort of growing, but growing on such a dark tangent. You need to make something beautiful”. And it was a good point. It’s the same as what Margaret said. As a contemporary artist why can’t I make something that’s beautiful and it be just as important as something that’s rigorously negative? And part of me thinks that that’s a Catholic upbringing. I went to a Catholic high school, and the idea of guilt, maybe it’s something to do with that, or entrenched Catholic Irish guilt from generations ago in Ireland, that I feel like as an artist that I have a responsibility to do more than just be covered in paint but to actually make comments about things that I feel. And I feel strongly about a lot of things, particularly the environment, and I spoke to Margaret at length in the lead-up to this Archibald and said “if I do win I want to talk about the environment and the fact there are people who still deny humans have anything to do with it”. She said “Ben, I agree, it’s ridiculous. I wouldn’t even address it because they don’t deserve the time”. But I said to her, it’s like denying Aboriginal people the vote. That’s how it will be seen in years to come.

Like the flat-earthers.

Exactly the same. It’s bizarre that I’m living here now and seeing it happen, and I just want to muzzle them and say “you guys are doing intense damage to my grandchildren’s lives and it’s time you stopped.”

Did you do this painting at Margaret’s house?

No, I actually made a steel-plate etching of Margaret. The marks that are on her face that are contained inside that shape, I actually did a hard-ground etching with a scribe and I just put in these little tiny marks and I wanted to leave her face blank. In fact, my idea was to leave even less marks on her face, the purest couple of little marks just to define her face. It’s hard for me to stop. The plate did that really. I also took photos and did some drawings. But scribing those marks, particularly that left eye, it’s Margaret. When I looked at it I thought , “I’ve drawn this wrong”, and I went back and photographed Margaret again. She looks at you with this piercing eye, and it’s so Margaret.

Is it raw canvas that shows through between the areas of paint?

It’s pre-primed linen.

What did you apply the oil paint with?

There’s everything. Brushes, and palette knives, and I scraped it off.

Do you feel this is an historic moment, given Dobell painted Margaret to win the Archibald in 1948?

Yeah, it is so amazing. [Ben said Margaret opened up to him with wonderful stories about Hill End where she worked with her great friends Russell Drysdale and Dobell.] She just opened up and told me all these very private stories about Russell Drysdale and Dobell. They’re like my mythical heroes, but they’re mythical, they don’t exist. There’s no recorded video footage of them, there’s no audio. And she’s it. She’s this portal to this period so long ago which has really informed who I am and what my work’s about. I’ve been looking at the Rabbiters painting from Sofala since I was about eight and it had such an emotive resonance for me.

Is your painting of Olley for sale?

Um, no.

Are you keeping it for yourself?

I don’t know. I’ve just been pulled aside then because people are talking about trying to buy it.

How does today compare with 1948?

How does today compare with 1948?

Well, I can cope with it much better now than I did then. Then I was just at the beginning of my career and I was on my way to Europe. So all that publicity when I came back, it took me years to be able to look at it. Here I’m at the end of my career, and I’m so pleased Ben won it. It’s a terrific painting. Barry Pearce and I gave him the Brett Whiteley scholarship, and I think that’s helped him.

How do the two paintings of you compare?

I’m a different person. I think the one Dobell did of me is the best Dobell. And I think this [Quilty’s work] is a great, great painting.

ArtWriter also sought Edmund Capon’s opinion.

You can’t go past that picture [the Quilty], but there’s a lot of good pictures this year. It’s one of the best Archibalds. It’s a very good show.

Your favourites?

Obviously the winning one. I like Jun Chen’s portrait, I like Charlie Waterstreet’s portrait by Adam Cullen – I’m alone in that. I like Tim Storrier’s and I like Rodney Pople’s and I like that one of Gemma Ward, too. So apart from the winning picture I seem to be somewhat out of step with the trustees. How unusual!

Below are a few more pictures I took at the announcement.

Elizabeth Fortescue, April 16, 2011

Vincent Fantauzzo wins the Packers Prize

Apr 8th

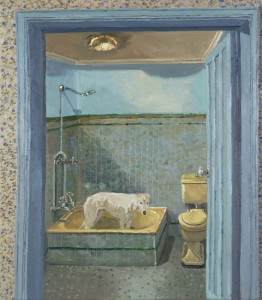

Vincent Fantauzzo won the Packers Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW today, with this portrait of the Sydney chef Matt Moran.

Vincent Fantauzzo won the Packers Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW today, with this portrait of the Sydney chef Matt Moran.

Opening of Wendy Sharpe exhibition at the S.H. Ervin Gallery

Feb 28th

Wendy Sharpe is one of the most exciting artists in Australia today, and her career is in full bloom. A survey exhibition of her work has just opened at the S.H. Ervin Gallery on Observatory Hill in Sydney, and ArtWriter was there to record the event for these pages.

Wendy Sharpe is one of the most exciting artists in Australia today, and her career is in full bloom. A survey exhibition of her work has just opened at the S.H. Ervin Gallery on Observatory Hill in Sydney, and ArtWriter was there to record the event for these pages.

The exhibition was full of the boisterous energy and love of life that fills Sharpe’s works, from her paintings to her drawings and sketch books, from her studies of the nude to her travel-scapes and her quirky portraits of herself and others.

The exhibition is called Wendy Sharpe: The Imagined Life. It is on display at the S.H. Ervin Gallery until April 10. A new DVD by Catherine Hunter and Bruce Inglis featuring Wendy, her partner Bernard Ollis, and ArtWriter, has been released to celebrate this landmark show. A new book has also been released.

I hope you enjoy these images. I enjoyed taking them.

Elizabeth Fortescue, February 28, 2011

Annie Leibovitz meets the Sydney news media at the MCA

Feb 11th

Annie Leibovitz at the MCA, Sydney, February 2011. Photograph of Leibovitz courtesy of Ben Symons and the MCA.

Invited media toured the show with Leibovitz, who spoke about selected works and answered questions from journalists. She walked into the exhibition alongside MCA director Elizabeth Ann Macgregor, looking elegant in black. Her demeanour was relaxed and chatty.

I covered this story for the Daily Telegraph, Sydney. But the opportunity to hear Leibovitz speak was so rare that I decided to upload my edited transcript of her comments on my website.

I would like to thank Ben Symons and the MCA for the photographs I have used on this page. Symons took them during the media call.

Elizabeth Fortescue, February 11, 2011

Annie Leibovitz: This show came out of a book which was an edit of work from 1990-2005. Susan Sontag had just died. As I sat down to start that edit I realised those were the years I was with Susan. I thought that what I would do is maybe look at this work as if Susan was looking over my shoulder. On some level, it was with Susan’s help. Susan had just died, my father had just died, my children were being born. So as I started to go through my work looking for a picture of Susan, I started to see this whole story here. I think at the time I was thinking, this is everyman’s story. This is not me. I saw birth, I saw death, I saw life. I thought, this is a bigger story than my everyday assignment work. I thought that I would hold these pictures out and make a story, and I pulled it together with the assignment work and I think it really worked together. I am the same person, I realised [both bodies of work] came from the same place. At the end of the show there’s two working walls. One wall has assignment work and one has the personal work, and those walls were reconstructed the way they actually were [while she worked on editing the show]. So, here we go. I should also say, in retrospect as time goes farther and farther away from creating this work, its focus is singular to that moment. I can’t go back and alter it. Last night and this morning I was thinking, I can never do this again. Put my family … I had second thoughts about putting even Susan in that position. I don’t know if you’ve read Joan Didion’s book, The Year of Magical Thinking, but it came out of this moment: oh this is so important, I’ve discovered love and birth and death and it’s a great story and I have to get it out. Now I’m a different person looking at this work.

Leibovitz stopped in front of her photograph of her father and brother, titled “My brother Philip and my father, Silver Spring, Maryland, 1988”.

This is just at the moment when my brother had his first baby. They were just feeling very… I think they were just identifying with each other. Literally Philip’s wife Niki and the baby were just off to the left as is my mum, and we were around the family pool, and when I started taking pictures I started at the San Francisco Art Institue. My mentors were really Robert Frank and Cartier-Bresson. And it was personalised reportage. That was my foundation, that’s where I started. This is the work that I brought to my assignment work. The more formal work came out of covers for Rolling Stone magazine when I started to pose people. But this is really the foundation to my work. You go through the show, you’ll see, I never stopped taking these picturtes. These pictures are always there.

Annie Leibovitz at the MCA, photograph courtesy of Ben Symons and the MCA

Leibovitz stopped in front of her nude photograph of Demi Moore pregnant. She spoke about how, although she got to know Bruce Willis and Demi Moore very well, she doesn’t “sit there and have Kellogg’s Corn Flakes with Mick Jagger. I understand that I’m there to take pictures, and I go on with my life. Hence the reason to build a life. When I was young I lived from assignment to assignment and I never went home. But at a certain point, you start to separate [work from life].

In any case, when Demi was pregnant with her first child I said, gee I’d like to photograph you pregnant. I’ve never really photographed a pregnant woman. I did these private pictures for them. They weren’t for publication. Very simple, portraits of Bruce and Demi together. So when Demi was pregnant with her second child and Vanity Fair asked me to do the cover of Demi, everyone at Vanity Fair was busy wondering, oh how are we going to take her picture, she’s pregnant, how can we do this without showing she’s pregnant? So I got out to California, Demi and I started taking pictures, and then part way through I said listen let’s takes some pictures for you, and I started taking some nudes of her. And I said you know what, this could be the cover. She got into it. You have to understand, working with Demi Moore is like being dragged behind a car. She would just literally take over whatever we did. She had more energy and ideas than anyone. It was a great collaboration. So we did this and I got back to New York and I showed this to Tina Brown and Tina was concerned about running it. She said she didn’t want to run it unless Demi Moore felt really comfortable about it, and there was a lot of conversations back and forth. It became more controversial than we expected. We had no idea it would mean so much. A woman when she is pregnant is expected at that time to not exactly parade it around. It’s true that not everybody looks like that [Demi Moore] when they’re pregnant. It was quite beautiful because doctors actually took the cover and framed it and put it in their offices. And of course now we have Britney Spears posing like this and everyone else. It became a celebration about being pregnant rather than it was a time that you should hide away. So it was a nice moment.

Leibovitz spoke about her photograph of the artist Cindy Sherman, where Sherman is in a line-up with a group of other women all dressed the same as her.

She is a great artist who photographs herself. I was extremely intimidated. I admire her so much. I didn’t really know what I was going to do. I went to see her at her loft in New York and she came to the door dressed like this. And I sat down with her and said what would you like to do? And she said, I like types. It just hit me. I said well why don’t we do 10 Cindy Shermans and you try to figure her out. She loved the idea. I found a casting agency who helped me find young actors and some were willing to cut their hair. I had about 15 other women here. Years later I was doing Claire Danes for the cover of Vanity Fair and I said very nice to meet you and she said oh no no we’ve met before, and I said where, how? And she said well you cut me off the end of the Cindy Sherman photograph. It’s true, I looked back and I did find her somewhere over here.

She spoke about her portrait of Leigh Bowery.

Lucian Freud did that whole series on Leigh Bowery. He [Bowery] came to my studio and he brought his partner. They do the birthing act and all these different things. I was enamoured with Lucian Freud’s paintings and I just wanted to do a nude. But [Bowery] didn’t want anything to do with it. So he came out in this outfit which is kind of opposite of nude, but in some ways it shows him more vulnerable than nude, because it just shows how much he, too, was trying to hide himself. It was an extraordinary outfit to say the least. On some level to be totally covered up has its own statement.

Leibovitz spoke about the portrait titled My mother, Clifton Point, 1997

Sometimes I’m asked what’s my favourite picture. Seems like a silly question and I’m always a bit reluctant to answer it because I don’t think I have a favourite picture. When you’ve been doing something for 40 years you realise that it’s the body of work that’s the strength. All the pictures sort of need each other. It’s a film. That’s how I see my work and I try to still do it until I drop, basically. Having said that, I jokingly say my mother was the first woman I met so I wanted to talk about my mother, and I knew that what I wanted to do was a picture of my mother …. My mother [in photos when Leibovitz was a child] wanted me to smile, and I began to distrust this smile because I thought it was canned. For this sitting in upstate New York I said mum are you OK? and she said I’m just worried that I’m going to look old. I knew that I wanted to photograph her and I wanted to see her age and I wasn’t going to take a pretty picture, but I wanted to show my mother’s strength and intelligence. So I was literally crying on my side of the picture. Printed the picture, showed it to my mother and of course she didn’t like it. My father didn’t like it either because she wasn’t smiling. The story has a nice ending. The picture was shown at the Corcoran as part of the women’s show and a lot of people came up to my mum and asked her for her autograph so she suddenly started to like the picture. So it probably is my favourite picture becuase this kind of moment is only going to happen between someone you love and loves you and it’s not assignment work. I was talking about this picture to someone who was interviewing me. They said, well she loves you. And I said no, no that’s not it, and I looked at it again and I said, you’re right! She does love me! It has a lot of layers to it and it just raises the bar. You can’t do this on your assignment work. It’s not the nature of it. It’s almost as if the camera isn’t there.

On her portrait of the Queen.

I did get this phone call from Buckingham Palace – it was almost like one of those joke phone calls where you go yeah, sure – that [the palace wanted Leibovitz to do a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II]. It wasn’t till right at the end of the shoot I found out why I was asked. This is a good story for someone who wants to do something and persevere. When I was working on the women’s book five years before, I sent Buckingham House [a letter] asking if I could do the same thing for the project, and the press secretary said she remembers that I wrote 5 years before for a sitting so they came back to me. Of course I was very excited about it, and as I started to do my research on the queen, she’s probably the most photographed woman in the world, realised that in the last few years no one has been photographing her very well. She seemed to be cast off to the side at some level. It’s hard if you’re an English subject to go take a nice picture of the Queen because you would be considered there’s something wrong with you. So I was very lucky being an American. At the time the movie The Queen had just come out with Helen Mirren, and I found her [the Queen] endearing one some level, so of course when I mentioned the movie to the press officer there was this long pause on the other end of the line! I had several ideas and they were all shot down and I was told basically it would be Buckingham Palace and that was it and I would have a half hour. I wanted to photograph the Queen outside in her garden. I planned it all very carefully and had the set-up all ready but I was constantly told she would go outside but she was not going to wear anything formal outside. A few days before I thought about Cecil Beeton’s backgrounds. I said well this is the digital age, i’m going to do my own background. So I went out and photographed the gardens in the back, and when the Queen walked in I actually showed her my contact sheets of the gardens and showed her what I was going to do. And I shot her against the grey background and placed her in front of the …. This is one of the three portraits. [With the others she used natural daylight coming into the room through the window.] [The Queen’s press office asked Leibovitz to appear in a BBC documentary being made about the Queen, and she reluctantly agreed.] They took some literary licence and said she was storming out of the shoot and literally she was storming into the shoot. At the very end of the shoot I said to the press secretary, 0h, I just love the Queen, she’s so feisty. Any of you here who are photographers know nine of 10 people … who wants to have their picture taken? So it was just another day for me. She actually went into the studio, she worked hard, she listened to my directions, she actually didn’t finish until I said thank you. She put the tiara on and off two times, and she literally had a sense of duty. The thing that hurt her most [about the documentary incident] was she said I’ve never walked out of a studio in my life. She was great. Everyone forgets she’s in her 80s. The major factor was I think I was interrupting her favourite television program. This is normal! She’s somethin’ else.

She spoke about the portrait of Nicole Kidman titled Nicole Kidman, New York, 2003

It was part of a cover story for Vogue magazine. I’ve worked with Nicole, many times I’ve come down to Australia and had the privilege and honour to work on the Baz Lurhmann movies, Moulin Rouge first of all and then of course Australia with Hugh Jackman. It was extraordinary to be on those sets. We just had a shooting in New York. I thought of doing it on a stage with lights. There’s very few people who can stand like that. I remember even saying you look so beautiful standing Nicole, and she said I love to stand. I’ve photographed her since she was a kid. She first came to the US and was always talented.

Her portrait of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, nude on the floor of their apartment in New York on the day Lennon was shot dead.

It’s probably my most famous picture. It’s such an interesting picture because everyone reads into it their story.

Asked whether she takes bad photographs …

Of course, all the time!

And what got her through the long, hard process of editing the exhibition?

What sustained me through all this was that I felt like she [her late partner Susan Sontag] would have been proud of me for what I did.